How I Choose Biologics Save

Clinical decision-making, occurring at the intersection of the ’art’ and the ’science’ of medicine, remains enigmatic and controversial. In rheumatology, there is little doubt that no area of specific decision-making has received as much attention as the decision to start biologics and if so, which one.

It has been pointed out, sometimes ad nauseam, that such choices must be ‘evidence-based’ - but evidence is not always easy to come by and the number of randomized trials that can reasonably be performed is easily an order of magnitude smaller than the number of clinically relevant questions and decision-making points.

So how do I decide to start a biologic?

I have to preface the answer by pointing out that Sweden, where I practice, has a very generous reimbursement system so the physician is given a free hand at prescribing most approved medications, and prescribed drugs are dispensed to the patient with only a small co-payment that is capped at around $300 per year. Having said that, physicians do experience increasing pressure from healthcare administrators to try to reduce the costs of prescription medication, and being a tax-payer in a fully socialized medical system makes you realized that it is your money that is paying for these very expensive drugs….

The choice whether to start a biologic or not is sometimes very easy: if the patient has severe rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, or psoriatic arthritis, and has failed treatment with multiple DMARDs there is really no doubt that a biologic is the way to go. Conversely, if the patient has mild disease that is active but having tried only one DMARD it would be quite absurd not to first explore the possibilities of adding another DMARD, switching to one, adding low-dose corticosteroids etc., before moving on to biologics. But in some instances the choice whether to start a biologic or not can be very hard. Some patients have moderately active disease despite ongoing treatment with DMARDs but it may seem wrong to try and manage them without the very likely benefit of a biologic even though there is always a chance that the next DMARD (or DMARD combination) could work. A recent Swedish study has demonstrated that in these ‘borderline’ cases, experienced rheumatologists do indeed make very different choices.

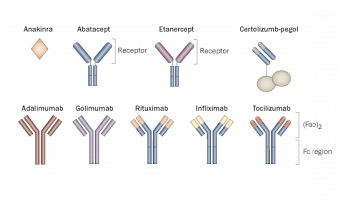

So which of the nine approved biologics (figure 1) do I start with?

Starting a biologic in practicality usually means starting an anti-TNF. This is largely the results that the first two anti-TNFs were approved in the late 1990s but the first non-anti-TNF biologic almost a decade later (not counting anakinra, which is less effective). Abatacept and tocilizumab are approved for use as first biologic, and clinical trials suggest they can be at least as effective in that situation as anti-TNFs. Therefore, some have argued that if these two biologics had been approved at the same time as the first anti-TNF they would have been used as often. I am not quite sure of that but I try to keep an open mind. As far as abatacept is concerned, it does appear to be as effective as anti-TNF and it may even have an edge when it comes to safety1. The only downside seems to be that the very rapid and striking improvement that occurs in some patients with anti-TNF (not with all!), where they tell you how they felt dramatically better the same day or the next day from when they took or received the first dose, is not encountered with abatacept. But for patients where safety issues are paramount I may choose abatacept as first-line rather than an anti-TNF.

With tocilizumab it is a different situation. The IL-6 antagonist may be as effective as anti-TNF and may even be more effective when used as monotherapy, but there are considerable differences when it comes to the safety profile. The most relevant differences in my opinion are, first, the fact that tocilizumab treatment is associated with several potential side effects that need to be monitored, particularly transaminase elevations and cytopenias. Rheumatologists are quite familiar with these issues from the classical DMARDs, but they do occur frequently with tocilizumab and this is a real difference compared to the anti-TNF biologics. It is fair to point out, as I myself have done, that these laboratory abnormalities did not lead to more serious consequences in the tocilizumab clinical trials2 – but it must be recognized that this was true only because the tests were followed closely and action was taken if they were abnormal. Second, tocilizumab may interfere with the CRP response to infection, which in a healthcare setting where CRP is used routinely by physicians in primary care and in emergency medicine to screen for infection is a disadvantage. And thirdly, there are some unresolved issues around tocilizumab such as the risk of GI perforations and the effect of cholesterol and lipid elevations. These issues may “blow over” with time, but it is also possible that real risks will turn out to be present in the long term.

So adding it all up, I would consider tocilizumab as a first biologic mostly if the patient has very severe disease and especially when I am forced to choose to use the biologic as a monotherapy.

Would I ever use rituximab as the first biologic – even though it is not approved for this indication? Yes I would, and what’s more, studies show that across Europe, rheumatologists are doing the same thing (but much less so in the US). Up to 20% of the use of rituximab may be as first biologic according to the CERERRA registry3. We informally polled colleagues in various countries about this and found that the most important reasons for choosing rituximab rather than an anti-TNF were a concern about tuberculosis and a concern about malignancy. As to the former, it is important to realize that risk for tuberculosis is a continuum. In some patients the risk is very clear – for example, they have radiographic signs of prior tuberculosis and a positive skin test – and then they will of course be treated for this before going to any biologic. Others have reasonably speaking no risk. But the clinician may rightfully be uncomfortable about a patient who has perhaps once been in an exposure situation, whose tuberculin or interferon test is borderline, and who is unlikely to tolerate INH or rifampin for some reason or other. In that situation, it would seem reasonable to use a drug not known to be associated with a risk for reactivating tuberculosis. Likewise, if the patient has had a malignancy many years ago, or a strong family history for various malignancies, it may seem safer to use B-cell depletion than TNF-antagonism, even though there is no direct evidence to prove that.

How about choosing among the anti-TNFs? As we all know the marketing efforts to ‘help’ us make this choice have been huge. I always have to smile when I see one more study of patient preferences that demonstrates how patients prefer, by a very wide margin, the subcutaneous route of administration over the intravenous one – and it so happens this study was sponsored by the makers of a subcutaneous biologic – or how equally convincingly they prefer to be treated intravenously over subcutaneously – and this study was sponsored by the company that markets an i.v. biologic. Likewise, the makers of the different subcutaneous anti-TNFs have tried hard to convince us of differences in terms of the molecular structure, pharmacokinetics, the frequency of administration, immunogenicity, implications for potential pregnancy, patient preferences etc. And so it’s a bit like Coke versus Pepsi and most of us conclude, wisely, that if it takes so much marketing to point out the differences then they are probably pretty similar. Therefore, when it comes to choosing between the anti-TNFs, I do try to weigh in the subtle differences between the medications in relationship to the specific patient profile, but I am also comfortable with the fact that the healthcare system may have the final word here based purely on cost. Having said that, if we are going to look at cost we need to do it wisely, because more and more data are suggesting that some anti-TNFs can be used at dosages lower than originally approved, especially in a ‘maintenance’ situation, and this could of course have a major influence on any cost calculations.

Finally, what to do when an anti-TNF has failed.

This question has been addressed in many observational studies and even to some extent in randomized trials, and the surprising answer seems to be that almost anything you do has a chance to work and these chances are pretty similar for each alternative4. Thus, going to another anti-TNF or going to one of the biologics with a different mechanism of action are both reasonable. Perhaps the most surprising result from a clinical trial in recent years, however, came from the RACAT trial and only as a small “secondary” finding: it turned out that patients who had failed etanercept had a pretty good chance to respond to the triple DMARD therapy5 – even though this is something not so many rheumatologist seem to be doing in practice.

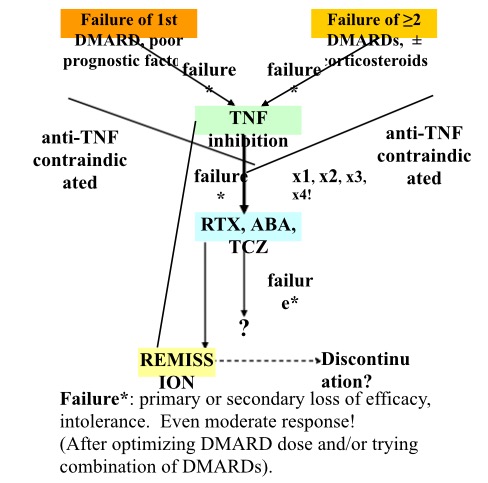

All things said, choosing a biologic remains quite a challenge in rheumatology. A simplified model for such choices is given in figure 2. As a profession, we can be pleased with the progress we have made in therapeutics, but I do hope and expect that there are still many ways that we can improve the way we are using therapies including biologics so as to ensure a better future for our patients.

Figure 1. The nine approved biologics for RA. Reproduced with permission.

Figure 2. A simplified decision-making scheme for biologics in RA. Reproduced with permission.

REFERENCES

1. Schiff M, Keiserman M, Codding C, et al. Efficacy and safety of abatacept or infliximab vs placebo in ATTEST: a phase III, multi-centre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to methotrexate. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:1096-103.

2. Genovese MC, Rubbert-Roth A, Smolen JS, et al. Longterm safety and efficacy of tocilizumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a cumulative analysis of up to 4.6 years of exposure. J Rheumatol 2013;40:768-80.

3. Chatzidionysiou K, Lie E, Nasonov E, et al. Highest clinical effectiveness of rituximab in autoantibody-positive patients with rheumatoid arthritis and in those for whom no more than one previous TNF antagonist has failed: pooled data from 10 European registries. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:1575-80.

4. van Vollenhoven RF. Switching between anti-tumour necrosis factors: trying to get a handle on a complex issue. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:849-51.

5. O'Dell JR, Mikuls TR, Taylor TH, et al. Therapies for active rheumatoid arthritis after methotrexate failure. N Engl J Med 2013;369:307-18.

6. van Vollenhoven RF. Unresolved issues in biologic therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2011;7:205-15.

7. Chatzidionysiou K, van Vollenhoven RF. When to initiate and discontinue biologic treatments for rheumatoid arthritis? J Intern Med 2011;269:614-25.