Late-Onset Disease: Different Age, Different Rules? Save

We’re seeing more patients develop rheumatic diseases for the first time in their 60s, 70s, or beyond. But are these truly the same diseases we see in younger adults, or do they behave differently, shaped by age-related biology, comorbidity, and the biases that influence medical decision-making?

Several abstracts presented at EULAR 2025 challenge us to reconsider how we diagnose and treat rheumatic disease in older adults. They point to differences not only in clinical presentation and immune profiles, but also in the care patients receive, and the hesitation with which that care is sometimes delivered.

At the Kumamoto Red Cross Hospital in Japan, Dr. Yusuke Imamura and colleagues (abstract POS0454) examined adherence to treat-to-target (T2T) strategies in newly diagnosed RA. Patients with elderly-onset RA (EORA, defined as onset at age ≥70) were significantly less likely to receive T2T-consistent care than those with younger-onset RA. Interestingly, this was not due to adverse events or comorbidities. The most common reason for non-adherence in both groups, particularly in EORA, was physician decision-making, including preferences or perceived improvements that didn’t meet the criteria. These findings raise an uncomfortable possibility: older patients may be undertreated because of age-driven therapeutic inertia.

But is this caution justified? Dr. Jiha Lee and colleagues (abstract POS0544) used data from the FORWARD registry to investigate whether older adults with late-onset RA (LORA, onset ≥60) are at a higher risk of serious infections (SI) after starting anti-TNF therapy compared to those with young-onset RA (YORA). Using a large propensity-matched cohort of patients aged 60 and older, they found no statistically significant difference in SI risk between LORA and YORA. Instead, long-term glucocorticoid use, not age of onset, emerged as the strongest predictor of infection. Yet ironically, LORA patients remain more likely to be maintained on steroids and less likely to receive biologics. These findings highlight an opportunity to better align treatment decisions with individual risk profiles, rather than relying on age alone as a guiding factor.

Clinical data can tell us what happens, but not always how it feels. To fill that gap, Dr. Signe Marie Abild and colleagues in Denmark (abstract POS0339-HPR) conducted qualitative interviews with older adults with RA and frailty. Their findings were sobering. Participants described frailty as a multidimensional burden, not just physical decline, but a psychological rupture. Themes included “a bitter farewell to the aging life once imagined,” a loss of autonomy in relationships, and deep frustration with a healthcare system that often failed to acknowledge them as whole people. These stories remind us that outcomes like remission or low disease activity, while critical, don’t capture the full lived experience of aging with RA.

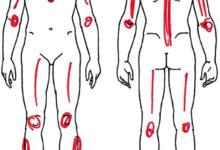

Similar patterns emerged outside of RA. In psoriatic arthritis, Dr. Han Niu and colleagues from Shanxi Medical University (abstract POS1044) compared early-onset PsA (≤40 years) to late-onset PsA (>40 years) and found striking clinical and immunologic differences. Late-onset PsA patients had higher joint disease activity (PASDAS) and more Th1 and Th17 cells, suggesting a more inflammatory, synovially driven disease, while early-onset PsA had more severe skin disease. These differences may explain why late-onset PsA often presents more like RA, and why precision approaches to therapy need to account for age at onset.

In ankylosing spondylitis, a parallel story unfolded. Dr. Binjian Lei and colleagues (abstract POS0531) found that patients with late-onset AS (>45 years) had higher disease activity (BASDAI, BASMI) and elevated NK and Th2 cell levels, compared to early-onset counterparts. These immune shifts suggest that age-related changes in the immune system, including immunosenescence and inflammaging, may underlie different disease trajectories, again raising the need for tailored approaches.

Taken together, these EULAR abstracts point toward a common theme: late-onset rheumatic diseases aren’t simply delayed versions of their early-onset counterparts. They have distinct biology, distinct burdens, and too often, distinct treatment pathways, pathways that may be shaped more by our perceptions than by patient needs.

We need to shift the question from “How old is this patient?” to “What does the age of onset tell us about their biology, risk, and goals?” Whether it’s rethinking T2T in an 80-year-old with active RA or recognizing synovitis-driven PsA in a 65-year-old with minimal skin disease, the message is clear: age matters, but it shouldn’t dictate care.

If you are a health practitioner, you may Login/Register to comment.

Due to the nature of these comment forums, only health practitioners are allowed to comment at this time.