What's New in Spondyloarthritis Save

Dr. Arthur Kavanaugh and Dr. Eric Ruderman gave an update on what's new in axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA) at the 2026 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium (RWCS) in Maui, Hawaii.

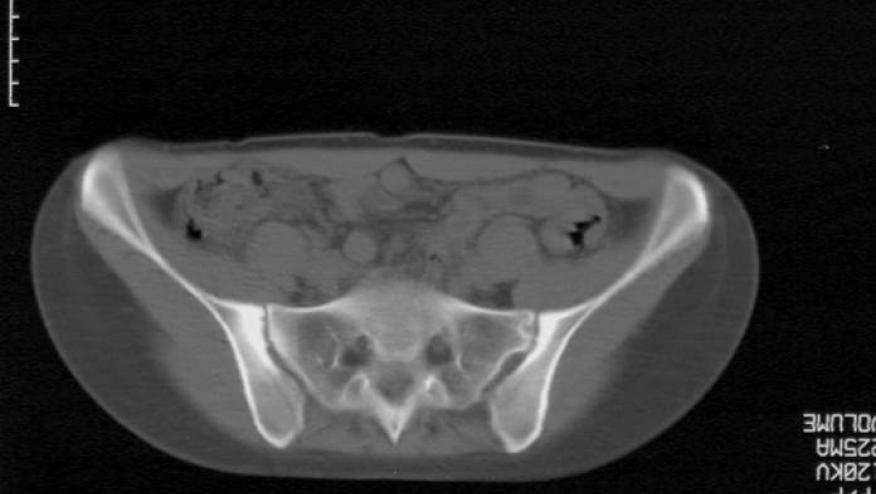

They opened with the renewed effort to refine axSpA classification, revisiting the classic goal of improving how confidently we identify the right patients for research. A newer proposal discussed landed at roughly ~80% sensitivity and ~90% specificity, and the 2025 revised classification framework reflects a clear philosophical shift toward objective findings. In the weight-based scoring, the heaviest hitters were imaging—either an MRI of the sacroiliac joints indicative of axSpA or radiographic sacroiliitis by modified New York criteria—followed by HLA-B27 positivity. The remaining clinical features, including elevated CRP and psoriasis, still mattered but were clearly less weighted.

From there, they pivoted to a complication we all associate with axial disease: acute anterior uveitis (AAU). When you look at the adjusted hazard ratios across biologics for axSpA, the conclusions were not surprising but still important to see again. Etanercept and secukinumab did not appear to have much efficacy in decreasing AAU onset in this population, whereas the TNF inhibitors—adalimumab, golimumab, and infliximab—showed a more favorable signal and did a solid job reducing AAU flares.

A very real-world disconnect between how many of us treat and what controlled data sometimes show, using secukinumab dose escalation as the example, was highlighted. Many clinicians escalate secukinumab to 300 mg monthly in under-responders rather than staying at 150 mg, and it often feels like a reasonable move when you’re trying to salvage a partial response. But they emphasized that in a phase 4 trial examining this strategy, there wasn’t a considerable difference with the higher dose. However, the endpoint was a tough one: inactive disease. I still think many of us see patient response with an escalation of dose and it’s certainly something I will continue to do in my practice.

The theme of practicality continued with the DRESS-PS trial, which examined whether adalimumab drug levels and anti-drug antibodies could predict successful tapering or discontinuation in patients with psoriatic arthritis or axSpA who were in low disease activity. This is the kind of approach many of our GI colleagues rely on routinely, but most rheumatologists don’t, and this study helps explain why. The conclusion was that drug levels and anti-drug antibodies did not successfully predict tapering or discontinuation outcomes in this population.

Drs. Kavanaugh and Ruderman then tackled what may be one of the most common and consequential decisions in axSpA care: what to do with TNF inhibitor inadequate responders.

Intuitively, switching to a different mechanism of action makes sense—Dr. Kavanaugh even acknowledged that it feels logical that if someone doesn’t respond to a TNF inhibitor, you’d move to a different class. But the ROC-SpA study pushed back against that assumption. In patients who did not respond to their initial TNF inhibitor and then switched either to an IL-17 inhibitor or to a second TNF inhibitor, switching to an IL-17 inhibitor was not superior to cycling within the TNF class. What this translates to in the clinic setting, at least for me, is that if a patient has only tried one TNFi, it may be worth trying a second TNFi before jumping ship to another mechanism of action. And this is something I try to tell my patients, too: “Sure, we can hop drugs, and I can help with that, but also understand that what we’re dealing with in this day and age is a great set of drugs, but it is not an infinite set of drugs.”

One of the more interesting late pivots in the talk was a reminder about a class of medications that no longer feels like it sits at center stage, even though it’s often right there in the background of axSpA management: NSAIDs.

We shouldn’t forget that “anti-inflammatory” is literally in the name, and that matters when we use MRI outcomes to make decisions. They described a UK study asking whether NSAIDs can affect imaging outcomes. The cohort included about 286 patients, and 51% had a positive MRI at baseline. Among those with a positive baseline MRI, 85% underwent a second MRI about 42 days later while taking an NSAID, and 20% had a negative second MRI. One could argue that some of those negative follow-up scans reflect normal variability, but the data also reinforce something that makes physiologic sense: NSAIDs may reduce MRI inflammatory signal. The practical implication is that an NSAID washout—something like two weeks—may be appropriate when obtaining subsequent scans intended to assess disease activity or treatment response, particularly in patients taking high-dose daily NSAIDs.

By zooming out beyond the typical rheumatology lens we can ask a bigger question: if axSpA is still being diagnosed late, how do we capture these patients earlier and how do we use new tools to diagnose and treat more effectively?

Data reviewed suggest that while awareness of inflammatory back pain among non-rheumatology clinicians is growing, it remains incomplete in ways that matter. In a large study of non-rheumatology physicians—including primary care, orthopedic spine, pain management, and PM&R—most were familiar with inflammatory back pain, but only 41% routinely assessed for it, and the study still found limited knowledge of imaging and labs. This is where rheumatology can have outsized impact by educating colleagues on the practical referral cues that go beyond “back pain” alone: peripheral arthritis, heel pain, psoriasis, uveitis, IBD symptoms, and a careful family history that probes for SpA-spectrum features. Drs. Ruderman and Kavanaugh also described an additional capture strategy from a Portland, Oregon group that partnered with chiropractors, which makes sense given how many patients with chronic back pain seek chiropractic care early. Working with four chiropractic offices, they referred patients with one or more SpA features to rheumatology, and about 12% of those referrals were ultimately diagnosed with SpA.

Finally, the promise and limits of AI in this space were discussed. A study applying deep learning to SI joint MRI reads showed that AI performance was overall close to human radiologists, but with a fair amount of disagreement, and they cited a positive predictive value of 84%. The question, though, is whether this is ready for prime time. A major challenge is that AI may be very good at detecting bone marrow edema, but bone marrow edema is not exclusive to axSpA—it can be seen with mechanical injury as well. If the algorithm flags edema, is it truly identifying axSpA, or simply identifying a signal that still requires clinical context and longitudinal follow-up to interpret correctly? In that sense, what we likely need next is not just better cross-sectional agreement studies, but longer-term studies that track patients over time to determine who ultimately proves to be “right”—the person or the computer.

If you are a health practitioner, you may Login/Register to comment.

Due to the nature of these comment forums, only health practitioners are allowed to comment at this time.