The Impact of Obesity on Psoriatic Arthritis Save

Developed under the direction and sponsorship of Lilly Medical Affairs and is intended for US healthcare professionals only

Up to 48% of patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) have concomitant obesity.1,2 Excess adiposity and PsA pathogenesis have mutually reinforcing mechanisms linked by shared inflammatory mediators.3-5 Understanding the impact of obesity on PsA may improve outcomes for some patients, as weight intervention is associated with achievement of targets of disease control.6,7

Learning objectives:

- Recognize the prevalence and clinical impact of obesity in PsA

- Understand mutually reinforcing mechanisms shared between obesity and PsA pathogeneses

- Explore evidence on how weight interventions

affect PsA disease activity outcomes

Concomitant obesity may decrease the likelihood of achieving PsA treatment goals

- GRAPPA treatment goals include achieving the lowest possible level of disease activity in all domains of disease8

- However, up to 70% of patients do not achieve MDA by 6 months of TNFi treatment9

- Patients with persistent symptoms despite at least one adequate trial of a targeted-synthetic or biologic DMARD may have complex-to-manage PsA10

- For these patients, comorbidities may contribute to inadequate treatment response.10 For example, up to 48% of patients with PsA also have obesity, 1,2 which is associated with:

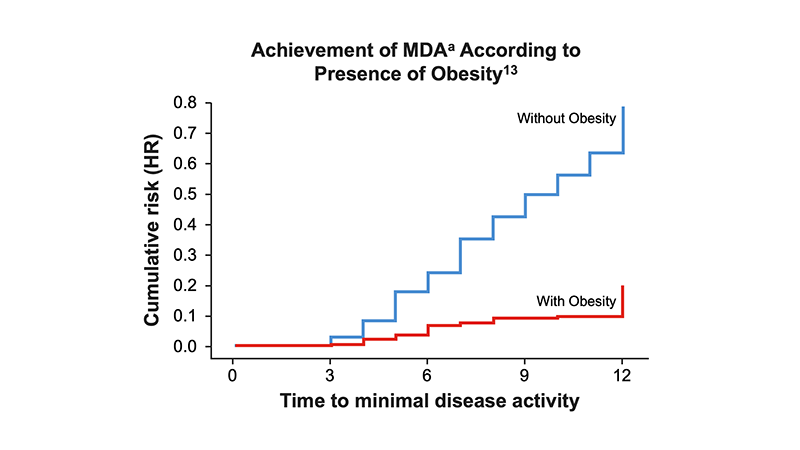

- Higher disease activity11

- Multi-drug treatment failure12

- Reduced odds of achieving MDA13

aMDA was achieved if at least 5 of the following 7 criteria were met: Number of TJC ≤1; number of SJC ≤1; skin manifestation none or almost none; patient’s joint pain by VAS (0-100) ≤15; patient’s assessment on PsA; activity by VAS ≤20; HAQ ≤0.5; enthesis points ≤1.

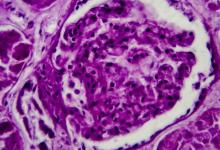

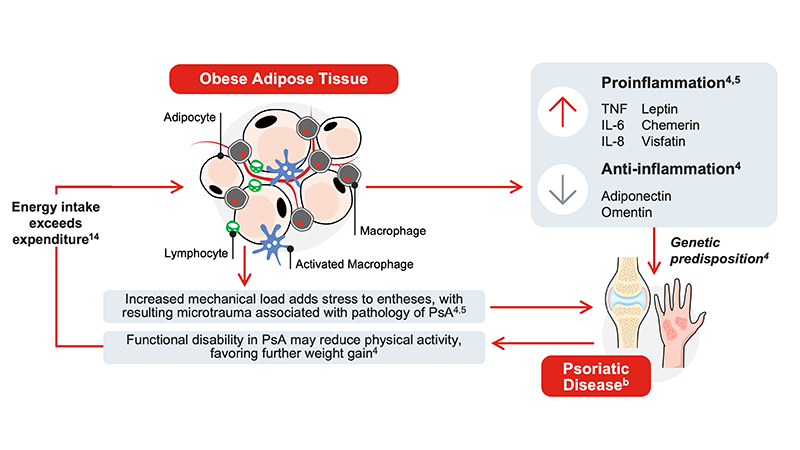

Obesity and PsA have mutually reinforcing mechanisms

- Excessive adipose tissue expansion induces low-grade systemic inflammation3

- Dysfunctional adipose tissue acts as an endocrine organ that secretes proinflammatory mediators relevant to PsA pathogenesis4, 5

- Obesity increases mechanical stress on joints, resulting in the microtrauma associated with PsA pathogenesis4,5

- Functional disability in PsA may reduce physical activity, favoring further weight gain4

bProposed mechanisms are based on current evidence and remain hypothetical; further research is needed to fully elucidate causal relationships.

Weight interventions improve PsA outcomes

- PsA treatment guidelines support obesity management in patients with active PsA and obesity

- GRAPPA recommends maintenance of a healthy weight to improve disease activity and minimize disease impact8

- ACR recommends weight loss for patients with overweight/obesity15

- EULAR recommends that comorbidities such as obesity, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease or depression should be considered managing patients with PsA16

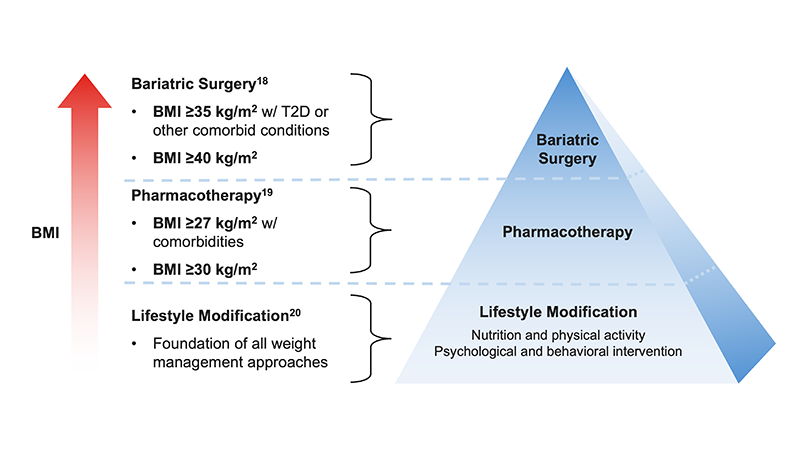

- The modalities of weight management include lifestyle modification (nutrition, physical activity, psychological and behavioral intervention), pharmacotherapy, and bariatric surgery17-20

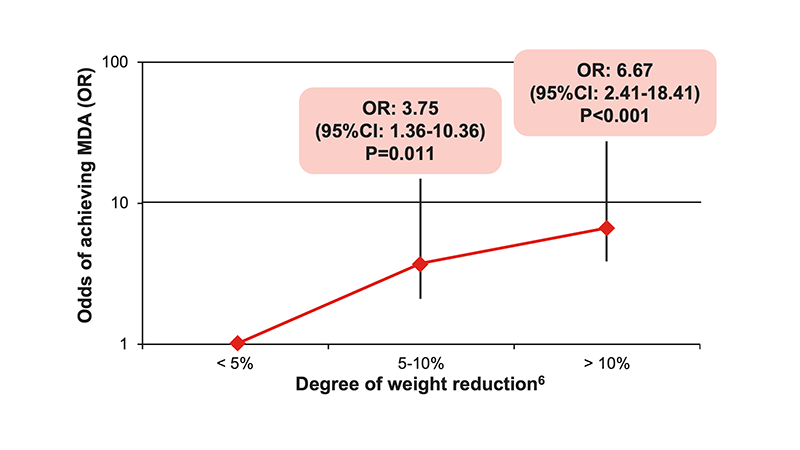

- Diet-based weight reduction is associated with achievement of MDA in patients with PsA and overweight/obesity starting TNFi therapy6

- ≥5% weight reduction is the major and independent predictor of achieving MDA6

- Odds of achieving MDA increase with higher percent of weight reduction6

- In the DIPSA trial, weight loss magnitude was significantly associated with improvement in clinical outcomes, including DAPSA, pain, fatigue, PsAID, and TJC. Degree of weight loss, rather than the specific dietary strategy, was the primary determinant of clinical benefit.7

- Several upcoming active control studies in the US will explore pharmacotherapy for patients with psoriatic disease and obesityc,d

| Trial | Phase | Patient population | Treatment arms |

| TOGETHER-PsA21 | 3b | PsA and obesity/overweight |

|

| TOGETHER AMPLIFY-PsA22 | 4 |

| |

| TOGETHER-PsO23 | 3b | Moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis and obesity/overweight |

|

| TOGETHER AMPLIFY-PsO24 | 4 |

|

cThe safety and efficacy of the molecules and uses under investigation have not been established. There is no guarantee that pipeline molecules will receive regulatory approval and become commercially available for the uses being investigated. The information provided about new disease states being studied is for scientific information exchange purposes only with no commercial intent. For more information on our pipeline, please visit https://www.lilly.com/discovery/clinical-development-pipeline. dThere is also a small (N=14) pilot trial in China studying semaglutide in patients with psoriasis and obesity.25 For more information on the individual molecules mentioned, refer to the prescribing information for ixekizumab (https://pi.lilly.com/us/taltz-uspi.pdf), tirzepatide (https://pi.lilly.com/us/zepbound-uspi.pdf) and semaglutide (https://www.wegovy.com/prescribing-information.html).

Summary

Obesity worsens disease burden for patients with PsA,11,12 and both diseases share inflammatory mechanisms.4,5 PsA guidelines recommend weight management for patients with active PsA and obesity.8,15,16 As weight reduction improves treatment outcomes,6,7 proactive discussion of weight management may help clinicians address this modifiable factor in PsA.

Abbreviations:

ACR=American College of Rheumatology; DAPSA=Disease Activity in Psoriatic Arthritis; DIPSA=Dietary Interventions in Psoriatic Arthritis; DMARD=disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; EULAR=European League Against Rheumatism; GRAPPA=Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis; HAQ=Health Assessment Questionnaire; HCP=health care provider; HR=hazard ratio; MDA=minimal disease activity; PsA=psoriatic arthritis; PsAID=Psoriatic Arthritis Impact of Disease; PsO=psoriasis; SC=Subcutaneous; SJC=swollen joint count; TJC=tender joint count; TNFi=tumor necrosis factor inhibitor; VAS=visual analog scale.

References:

- https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/Default.aspx (Accessed January 8, 2026).

- Data on file. Lilly USA, LLC. DOF-IX-US-0341.

- Favaretto F, et al. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2022;23(1):71-85.

- Porta S, et al. Front Immunol. 2021;11:590749.

- Kumthekar A, Ogdie A. Rheumatol Ther. 2020;7(3):447-456.

- Di Minno MND, et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(6):1157-1162.

- Eder L, et al. Abstract presented at: ACR 2025. Abstract 2690.

- Coates LC, et al. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2022;18(8):465-479 (updated 18(12):734).

- Mease PJ, et al. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2024;83:687-688.

- Proft F, et al. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2025; doi:10.1038/s41584-025-01329-3 (Ahead of print).

- Galarza-Delgado DA, et al. Int J Dermatol. 2024;63(1):e1-e2.

- Haberman RH, et al. Arthritis Res Ther. 2025;27(1):46.

- di Minno MN, et al. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013;65(1):141-147.

- Guo Z, et al. JID Innov. 2022;2(1):100064.

- Singh JA, et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(1):5-32.

- Gossec L, et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2024;83(6):706-719.

- https://obesitymedicine.org/about/four-pillars/ (Accessed January 8, 2026).

- Eisenberg D, et al. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2022;18(12):1345-1356.

- Pedersen SD, et al. CMAJ. 2025;197(27):E797-E809.

- Garvey WT, et al. Endocr Pract. 2016;22(7):842-884.

- https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06588296 (Accessed January 8, 2026).

- https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06864026 (Accessed January 8, 2026).

- https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06588283 (Accessed January 8, 2026).

- https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06857942 (Accessed January 8, 2026)

- https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06937060 (Accessed January 8, 2026).

MMAT-01025 © 2026 Lilly USA, LLC. All rights reserved.