Pain in Psoriatic Arthritis Save

Pain is typically ranked by both patients and physicians as the most important symptom of psoriatic arthritis (PsA) to assess and treat. Pain is a key feature of inflammatory arthritis, and impacts all aspects of a patient’s life, impairing ability to physically function and engage in meaningful life activities. Further, there is a significant association between pain and depression. The ability of a treatment to ameliorate pain is one of the principle measures of its effectiveness. Thus pain improvement or worsening are key determinants of shared decision making about treatment in PsA.

Although the predominant concept of the etiology of pain in PsA is that of inflammation in peripheral joints, entheses, and bone signaling through peripheral nociceptive fibers, perceived as pain in the central nervous system, it is actually more complex than that. There are three categories of pain that patients experience: nociceptive, nociplastic, and neuropathic.

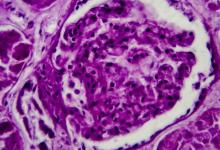

Nociceptive pain is a result of activation of afferent sensory neurons known as nociceptors, resulting from tissue inflammation and damage caused by inflammation and excess pro-inflammatory mediators in joints, entheses, and spine, as well as skin plaques in patients with PsA. This nociceptive signal is sent to the spinal cord and on to pain processing centers in the brain such as the somatosensory cortex and insula. Documentation of this form of pain signaling has been corroborated by sophisticated neuroimaging techniques. In addition to nociceptors in joints, common with other inflammatory arthritides, PsA patients also transmit nociceptive signals from peripheral and spinal entheses and bone, as well as skin plaques. Furthermore, there is recent evidence of a neurobiological relationship between pain arising from musculoskeletal sites and itch arising in skin plaques; dysregulation of nociceptive neurons in skin contribute to both inflammatory changes of the skin and hyperalgesia, augmenting the body’s pain experience.

Nociplastic pain is the result of a phenomenon called “central sensitization”, in which there is increased production and activity of nociceptive neuropeptides in the dorsal root ganglia, spinal cord, and various brain centers involved with processing pain. Nociplastic pain can be experienced even in the absence of peripheral tissue injury and peripheral nociception. This augmentation of central nociceptive neuropeptide signaling, pain hypersensitivity, occurs more frequently in patients with chronic immune-mediated inflammatory conditions as well as chronic pain states, is not directly correlated with peripheral inflammation, and has complex influences including genetic and psychosocial factors, and sex. One manifestation of this phenomenon is known as fibromyalgia, often accompanied by fatigue and sleep disturbance, seen in approximately 15% of patients with PsA and other rheumatic diseases. However, even in patients without overt evidence of fibromyalgia, varying degrees of central sensitization can be observed in up to 40% of PsA patients. These patients will record more severe disease activity measured by composite scores with subjective elements such as tender joint count, enthesitis scores, patient pain and patient global and be less likely to achieve high thresholds of treatment response such as Minimal Disease Activity (MDA)1.

Neuropathic pain represents increased nociceptive pain signaling due to a lesion or disease of the peripheral or central nervous system, which leads to augmented pain response. For example, dysregulated neurons in the skin are known to not only have a relationship with psoriasis lesions and itch, but also the phenomenon of hyperalgesia, which can influence the patient’s overall experience of pain.

As can be seen, sorting out the various contributions to the PsA patient’s pain experience can be difficult, not only because of multiple contributing sites of inflammation (joints, entheses, spine), but also how much is due to inflammation causing nociceptive pain vs. nociceptive or neuropathic contributions.

If the patient has a pain level of 5 out of 10, yet no swollen joints or elevation of CRP, is the pain arising from inflammation in entheses or spine, not as readily detectable on physical exam, or is it coming from the patient’s concomitant fibromyalgia? If the former, perhaps documented by power Doppler light-up of ultrasound of entheses or MRI of the spine, then discussion about switching immunomodulatory medicines may be in order. If the latter, then it is inappropriate to switch the patient’s PsA-specific medication and better to engage in discussion about fibromyalgia/central sensitization with the patient and consider treatment, either pharmacologic or non-pharmacologic, or both.

Another example is that if a patient has both PsA and painful peripheral neuropathy, it may be helpful to try an agent like gabapentin to diminish the neuropathy pain and any contribution it may have to augmented pain experience, hyperalgesia. Take note that nowhere in the above discussion have opioids been mentioned. Each of the potential categories of pain experience can be addressed without the need to resort to opioids. Indeed, there is evidence that chronic opioid use can increase the phenomenon of hyperalgesia or augmented centralized pain, and thus this class of medication should be avoided.

In summary, rather than thinking of pain as a unitary symptom arising from peripheral inflammation in PsA joints, which is to be mainly addressed with anti-inflammatory/immunomodulatory medication, think of it as a more complex and nuanced phenomenon that may be arising from multiple sources. These may include less obvious clinical domains such as enthesitis or spondylitis, fibromyalgia of the broader phenomenon of central sensitization, or neuropathic sources, including the skin. Education of the patient about the potentially complex sources of their pain experience will improve care and increase trust in the patient-clinician relationship.

1. Mease P. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2017 Jul;29(4):304-310

If you are a health practitioner, you may Login/Register to comment.

Due to the nature of these comment forums, only health practitioners are allowed to comment at this time.