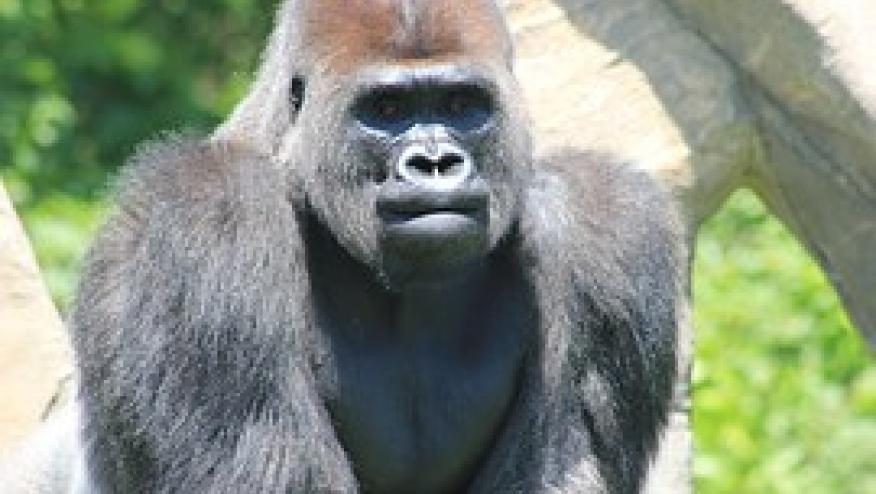

Drug Safety Risk Communication: The 800 lb Gorilla Approach Save

Discussions on drug safety can be as treacherous as quicksand for the patient and physician. You may not know enough about it and it’s probably best to avoid it. What the physician knows and what the patient perceives may not be in sync. Here’s a recent clinic conversation:

Doctor: Mrs. Jones, I see that you’re still on meloxicam and prednisone, but did not yet start the injectable biologic we spoke and prescribed at last visit. Why are you not on the new medicine?

Ms. Jones: I know, I was going to start it but when I researched that drug and it scared me. Then I started hearing more and more about it – on the TV and my cousin use to take it. It seems too dangerous for me.

Doctor: Well, there may be side effects that are concerning. But you may not realize the frequency of those side effects. Most of the scary ones, like cancer, lymphoma, lupus and tuberculosis, occur at a rate of one in a thousand. Let me repeat that’s 1/1000, about the same as getting a hole in one in golf or getting hit by a bus crossing the street. The more important risk is the 800 lb. gorilla in the room – your rheumatoid arthritis. If untreated, your disease will worsen and the consequences of that are usually ugly or devastating. The side affects you are worried about are flea-sized compared to the 800 lb. gorilla sized disease you have – RA.

There are many reasons patients don’t or won’t take prescribed medications. High on the list is the physician's inability to convey both the need and the safety of a drug. While a good doc will know the safety profile of a particular drug, its common adverse events and dangerous complications, he/she may not have the time or effective strategy to share the knowledge.

The first few visits with a newly diagnosed patient are crammed with diagnostic challenges, infopenia or overload, hurdles of patient acceptance and education, and new drugs that are unspellable, unspeakable and sometimes unaffordable to patients. Somewhere amidst the chaos there needs to be a discussion on the risks and benefits of newly introduced therapies.

In 2007, I surveyed 494 US Rheumatologists on the issue of drug safety. Nearly 88% believed patients got most of the “safety information” from the doctor’s office and over 98% claimed it was their responsibility to educate the patient on drug safety. However, the #1 educational tool used was info and brochures provided by the drug manufacturers. While most education rests with physician’s office, the materials and time are insufficient.

Despite our efforts, patients may not take a drug or even fill the prescription. According to Consumer Reports, half of patients assume grave risks by skipping doses, taking expired medications, or not filling a prescription. According to the Analysis of the Commonwealth Fund 2007 International Health Policy Survey, patients in the United States are 5-10 times more likely to not fill a prescription with nearly 23% of prescriptions going unfilled (higher in the elderly and low income groups). Annals of Internal Medicine published a study by Tamblyn showing that nearly 33% of all prescriptions go unfilled - higher with expensive drugs and chronic conditions.

Nonadherence is also a product of risk aversion and complicated by inexperience in making value-based choices. Dr. David Pisetsky wrote on rules on safety (The Rheumatologist, July 2009) and stated that the best way to reduce the side effects of a drug is not to prescribe it (or don’t use a risky drug when an alternative exists). The balance of potential benefits and risks of a particular therapy must be clearly understood by both the patient and prescriber.

First-time car buyers, newly engaged couples and patients are naturally risk-averse. Hence the belief that there may be more harm in taking meds than in avoiding meds. When confronted with ambiguous situations, decision avoidance may appear to be the safest option. Such choices are usually anchored in what is not known, and hence, may not be the wisest. Decisions built on a foundation of fear are unlikely to be productive. I have previously written about why patients are reluctant to change, owing to a “the devil you know - than the devil you don’t" rationale and the Ellsberg paradox, wherein ambiguity aversion drives decision making. If fear (or risk aversion) is the foundation of safety concerns, then time, experience and education are necessary to correct the risk: benefit balance and concerns.

So, here is the approach to risk communication that works best for me.

- Accept that you need help and a strategy. Communicating risk is something we are not good at. But that can be changed. Especially if you make it a first time, every visit objective, for every patient and for almost every drug. This may take a lot of time and time is already in short supply. Hence, you need tools, handouts, a consistent message, rules to live by and a plan that is better than data or medicolegal jargon – it’s a script to optimized therapy, treatment success and happy trails.

- Gorilla vs. the flea (see vignette above). It is the physician’s job to worry about side effects, but also to give the patient perspective on the effects of the (untreated) disease versus the potential hazards of the new drug. The disease (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis) is clearly a progressive disorder that is far more damaging or devastating than the drug the patient is worried about – either because of the internet, water cooler gossip, or the 3 page pharmacy shameful side effect listings. The physician has to communicate the magnitude and potential of their disease and the comparative risks of the disease versus drug:

- Patient must understand the magnitude of their problem. Is this a large problem (the 800 lb. Gorilla of RA) or a small problem (Flea or small issue)? If they understand that the 800 lb. Gorilla is the active, ever-present disease that will, with a high degree of certainty, maim, derange, damage, or kill them, it may be easier to accept the value of a new medication that aims to abrogate RA's evil outcomes first and considers risks secondarily.

- Comparative Risk: You need to be clear and instructive in your communication about risk, especially for the most common adverse events (e.g., “10% will develop diarrhea”) and the most serious (e.g., “there is a 1 in 1000 chance of lymphoma"). I find it useful to bring the patient back to reality with the 800 lb. Gorilla analogy. Use visual aids like the speedometer or 1000 dot/person grids. Go to Dr. John Paling's site on Risk Communication.

- More info may be more confusing. Explain up front that all drugs have side effects and that many they read or hear about will never happen to the vast majority of patients. Point out that the 3 page drug handout (package insert) from the pharmacy has over 15,000 words– both designed as a referenceable compendium of all effects reported and to serve as legal disclosure from the manufacturer to defend against lawsuits for the dreaded, fatal, pink-pinkie syndrome*.

- Doomsday thinkers. Patients afflicted with chronic or unfortunate disease often believe the cloak of safety has escaped them. At least twice a day I hear from patients “oh don’t worry, it may be rare.. but I always get the bad stuff” or “I don’t respond like others to most medications” or “I’m allergic to everything”. Such statements are usually spoken by patients who are already on many medications. They may also be the defense of folks who have never trusted a doctor or drug – because they have been let down by doctors and drugs. It’s your job as the doctor and prescriber to earn their trust and convince them of your ability and concern. This is difficult.

- Speak from strength. When confronted with the reluctant patient or doomsday thinker – I may have to remind them, “this prescription and advice is the result of my being in practice for 25 years, having cared for thousands of patients in your same situation, using a drug that took 12 years to develop, at a cost of over $1.3 billion dollars; a drug that has been used by over a million people worldwide and this therapy is approved of by the FDA, your insurance company and has become a standard recommendation in treatment guidelines drawn up by the worlds experts and the American College of Rheumatology.”

Lastly, it’s important to understand why this is such a challenging task and confusing area for patients. Safety communication is becoming more and more complex when considering:

- Each new drug has a safety profile that may be evolving;

- Patient needs and understanding of drug safety varies widely and may change over time;

- Product label (AKA package insert) that are difficult to read or learn from (and physicians seldom read the package insert);

- Insurers, 800-telephone support lines, pharmacists, PCPs and even you the prescriber keep asking the same questions: “have you had any infections, rashes, fevers, tumors, unusual reactions to the medication?” It’s no wonder patients lay awake at night thinking, “this drug will probably kill me moreso than this disease”;

- Patients largely get their safety information from sources that worry physicians: 1) Pharmacy print outs; 2) direct-to-consumer advertising (primarily TV ads) that sell drug while scaring the patients who have to take the same med in the morning; 3) concerned friends and relatives who have negative stories to tell and 4) Pharmacists and colleagues in medicine (PCPs, surgeons, dentists, nurses) who get their drug safety education from the same DTC ads noted above.

- The longer someone deals with and affliction or takes a medicine the more opportunities they have to be confronted by “the bad story” about that drug – which becomes the anecdote that unnerves the patient;

- Not wanting to change Rx: Fear of losing control of RA control and fear of side effects that seem more certain than the speculative benefit of a drug;

- Risk adversity is magnified by previous side effect experience

- Those with a high desire for information include females, younger, and educated patients

- Imagine how overwhelmed a patient is after being give a new diagnosis and a new drug and therapeutic plan! Compound that with a pharmacy bill, new drug and a 2 page print out covering all the risks (without priority) that they are supposed to take home and read. Of course all this seems quite unbelievable and overwhelming to the point that most patients then seek a “second opinion” from: a) the internet; b) their daughter-in-law the pediatric nurse; c) a good friend/neighbor who is either a chiropractor or neurologists. Recognize that b) and c) get their info from the TV ads and the internet – often a wasteland of misinformation.

- Lastly the hoops and hassles of insurance, pharmacies, co-pays, lab testing and doctor visits lead hoop jumping surrender and high rates of nonadherence, self-dosing or drug cessation.

Average Person Risks

- 1/7 Lifetime risk of cancer

- 1/30 Odds of having twins (odds of triplets is 1/8100)

- 1/50 (2%) Lifetime risk of lymphoma

- 1/63 Odds of getting influenza (without vaccination)

- 1/84 Odds of a car accident (odds of dying in car accident = 1/112 to 1/470)

- 1/175 Odds of an IRS audit

- 1/100 Odds of death from drowning (odds of death from drowning in bathtub 1/10,000)

- 1/2739 Lifetime risk of dying from falling down stairs

- 1/8015 Chance of Plane Crash (lifetime risk of dying from plane crash 1/11 million)

- 1/700,000 Chance of being struck by lightning

- 1/3.5 million Odds of being bitten by a shark

- 1/175 million Odds of winning Powerball

All odds are subject to conditions. For instance, your odds of dying in a car crash are much greater if you are in a small car (compared to an SUV). Or, your chances of having twins are much greater if your over 45 yrs. of age, tall, obese, Nigerian, living in Massachusetts or Connecticut and have a personal or family history of having twins.

** The fatal pink pinkie syndrome is an imaginary, fictitious disorder that frequently disrupts the author's sleep. To date, the only person afflicted with this potentially drug related complication is the author and only between the hours of midnight and 6AM.

If you are a health practitioner, you may Login/Register to comment.

Due to the nature of these comment forums, only health practitioners are allowed to comment at this time.