Gout and the Social Determinants of Health Save

Sir Michael Marmot is one of my medical heroes. Despite appearing to be the epitome of British establishment medicine, in fact he was raised in Australia and received his medical degree from the University of Sydney, so we like to claim him as one our own.

He is best known for his work as a pioneer in the field of the social determinants of health. This began with his seminal work on the Whitehall study, which tracked mortality among public servants in the UK and, to everyone’s surprise, did not find an excess of cardiovascular deaths among the highly stressed upper strata of the workplace hierarchy, but instead showed a robust inverse linear association between mortality and position in the social hierarchy. The higher you are in the social structure, the less likely you are to suffer from chronic disease and premature death. Importantly, this association was found in a relatively affluent population, where material deprivation was not a concern, and suggests that social factors are fundamental upstream drivers of a variety of health-related behaviours and experiences that are primarily responsible for the distribution of chronic disease within society - or what Marmot has termed the “causes of the causes”. Such as association has since been confirmed in a variety of different social contexts and for a wide range of chronic disease states. Striving to achieve good health, then, is the province not just of the individual, but also of society and the policy-makers who influence its structure.

“The stark fact is that most disease on the planet is attributable to the social conditions in which people live and work.”

Stonington & Holmes, PLoS Medicine 3(10):1661(2006)

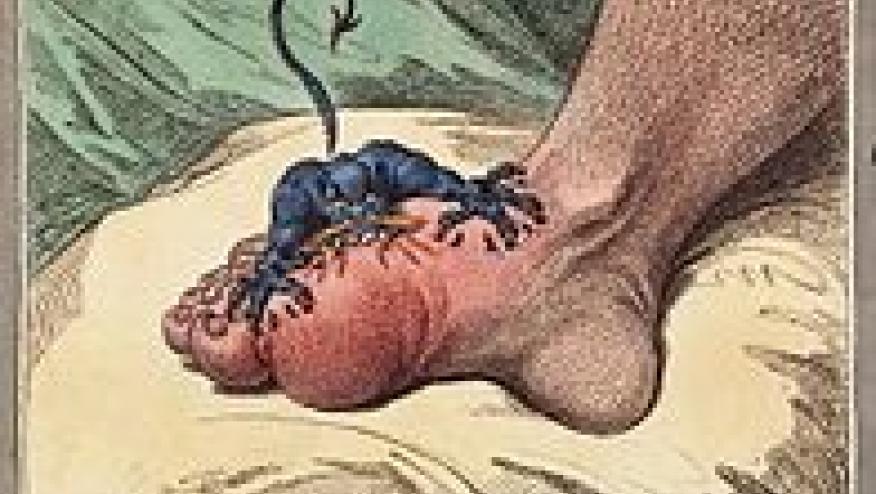

During a fascinating gout session on October 21, Hyon Choi presented an important paper (abstract 874) which used data from the Health Professionals Follow-up Study to try to understand the rapid increase in the incidence of gout in recent decades. Data from over 44,000 men in the HPFS demonstrated that five factors (BMI, diet, diuretic use, alcohol consumption, and vitamin C supplementation) accounted for 80% of the population attributable risk of incident gout. In other words, if we could eliminate poor diet, obesity, and alcohol use, we could largely prevent incident gout. Clearly this is a goal best addressed at the social level rather than the individual level - it is not so much the individual’s decisions about diet and alcohol that is important in the population, but much more the structures that influence these decisions: the “causes of the causes”. Gout is not just a highly-treatable disease, it is potentially highly-preventable. For me, this paper is a call to action both for rheumatologists and for our politicians and policy-makers. Or, in the prescient words of the great Rudolf Virchow:

“Medicine is a social science and politics is nothing else but medicine on a large scale. Medicine as a social science, as the science of human beings, has the obligation to point out problems and to attempt their theoretical solution; the politician, the practical anthropologist, must find the means for their actual solution”

If you are a health practitioner, you may Login/Register to comment.

Due to the nature of these comment forums, only health practitioners are allowed to comment at this time.