Glucocorticoids in SLE: how to start, how to follow, how to stop Save

More than 70 years after their first use in rheumatology by Philip Hench, glucocorticoids (GCs) continue to be one of the main weapons to fight systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). No other available medication results in such a rapid reduction of lupus activity; however, a wide range of side effects associated with the prolonged use is the other side of the coin of GCs. Damage accrual and a wide impact on patients’ quality (even quantity) of life is too high a price to pay. Therefore, current guidelines recommend limiting the use of GCs by coining the new concept of “bridging therapy”, that is, use GCs when the disease is active and get rid of them as soon as you can. This way of thinking is conceptually attractive, however, the formula for translation to real life settings is not included.

The delicate balance between the efficacy and toxicity of GCs can be actually explained by the molecular mechanisms underlying their biologic effects. GCs are in fact hormones, derived from the physiological steroid cortisol. All the effects of GCs on glucose and lipid metabolism as well as the activation of bone resorption are mediated by genomic mechanisms, through the activation of several genes within the nucleus of the effector cells (a process known as transactivation). In addition, the genomic way also promotes the inhibition (transrepression) of a number of pro-inflammatory genes. As the genomic way becomes more activated with increasing doses of GCs, both the anti-inflammatory and metabolic effects rise in parallel, therefore, more immunoregulation always means more metabolic toxicity. Both peak at doses around 30-50 mg/d of prednisone, depending on a number of individual factors.

But, please, do not despair, there is some good news -in the form of a second, non-genomic way of action of GCs. Through different, extra-nuclear pathways, GCs can recruit additional anti-inflammatory effects which come into play at doses over 100 mg/d, peaking at 250-500 mg/d. If used over short periods of time, this so-called pulse therapy offers stronger and faster immunomodulatory activity, virtually free of the genomically-mediated metabolic side effects. This is the rationale for the use of methyl-prednisolone pulses (MP) in scenarios of active lupus.

At the other end of the spectrum, prednisone at low doses ≤5 mg/d saturate less than 50% of cytosolic GC receptors, and thus do not activate more than half the genomic way. Such doses may not be enough to induce remission in a flaring patient, but can help to keep SLE in remission combined with hydroxychloroquine +/- immunosuppressive drugs. In terms of toxicity, such low doses do not result, in global terms, in a substantially increased risk for damage.

Therefore, based on the pharmacological and clinical evidence and the balance between benefits and risks, high-dose oral GCs (>30 mg/d) must be always avoided in the management of SLE, while low doses ≤5 mg/d can be maintained during prolonged periods of time. Our scheme could be headlined as “taper quickly, withdraw slowly”.

- Hydroxychloroquine is the cornerstone of SLE therapy and also helps reduce the dose of GCs, thus it should be always maintained except in the very unusual event of well-confirmed toxicity.

- Mild lupus flares (non-extensive rash or arthritis/tenosynovitis, for instance) can be treated with minor increases in the dose of prednisone, up to 7.5-10 mg/d, with rapid decrease to 5 mg/d within a few days.

- For moderate to severe flares (widespread skin or articular disease, pleuritis/pericarditis or vital organ involvement, such as lupus nephritis), or for mild flares not rapidly responding to the above regimen, MP 125-250-500 mg/d x3 (depending on severity) offer a more rapid onset of action and allow using lower doses of prednisone, up to 30 mg/day (remember, never above that point), with rapid tapering to 5-2.5 mg/day within a few weeks (see in the Figure our scheme for lupus nephritis and severe lupus in general).

- Such a reduction must be accomplished regardless of the evolution of SLE, which in case of persisting activity should be treated by adding up immunosuppressives and, if needed, biologic drugs, with repeated MP offering bridging therapy until other treatments are fully effective.

- The wider use of biologic drugs, such as belimumab and the recently licensed anifrolumab, has been proposed to reduce GC exposure; however, the limited experience with the latter and, overall, the lack of affordability (of both) for many patients, make this option limited from a global perspective. As said, they could be individually used in refractory patients to help them achieve prolonged remission on prednisone doses ≤5 mg/d. On the contrary, they should not be started with the only purpose of stopping low-dose GCs in a stable patient.

In summary, the solution for the bad usage of GCs is not proscription, but using them well.

Table. Rapid guide for the good management of glucocorticoids in patients with Systemic Lupus Erythematosus.

|

HCQ: hydroxychloroquine; MP: methylprednisolone pulses.

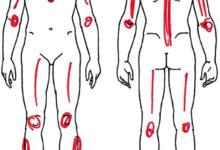

Figure: The Lupus-Cruces scheme for lupus nephritis and severe lupus.

Join The Discussion

Guillermo: How timely. I just read your excellent article this past weekend (Porta et al), and it was excellent. I highly recommend all rheumatologists and APPs who treat SLE patients to read it. Print out figure 3 from the article and pin it up somewhere. If we all did this (along with abiding by the 2023 EULAR Guidelines), there would be many more SLE patients in remission and off steroids.

Here is the reference to the article: Glucocorticoids in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Ten Questions and Some Issues. J Clin Med. 2020 Aug 21;9(9):2709 at https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/9/9/2709

Thank you Donald, I really appreciate your comments.

We are practicing this way for years and the results, as shown by our clinical research, are really good for patients, very low toxicity and high remission rates, also for renal disease. We are very happy this way of approaching lupus therapy is spreading out.

If you are a health practitioner, you may Login/Register to comment.

Due to the nature of these comment forums, only health practitioners are allowed to comment at this time.