Addressing Disparities and Unequal Burdens in ILD Save

Interstitial lung diseases (ILDs) represent a complex spectrum of conditions that share one unifying truth: they are almost always serious, progressive, and life-altering. But for many patients, the burden of disease does not fall evenly. We are increasingly learning that where you live, who you are, and the resources available to you, can strongly influence how ILD develops and worsens. Understanding these disparities is not about pointing fingers. Rather, it is about uncovering opportunities to deliver better, fairer care.

One of the most striking patterns seen across multiple cohorts is the age at which ILD is diagnosed. For example, studies show that Black patients are often diagnosed nearly a decade earlier than their White counterparts, sometimes in their mid-50s rather than late 60s. Once diagnosed and carefully matched for disease severity and access to multidisciplinary care, survival can be similar—or in some cases even longer—than in White patients. Yet because disease begins earlier in life, age at death is also younger, underscoring a profound additional burden on work, family, and long-term planning. This paradox highlights both the resilience seen in survival curves and the urgent need for earlier detection, tailored support, and strategies that extend not just years lived with disease, but years lived overall.

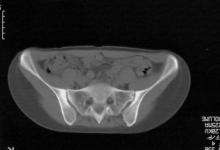

Geography is another lens through which disparities become clear. Living near major roadways or in areas with higher air pollution has been consistently associated with worse lung function and higher rates of disease progression. Importantly, this effect does not distribute evenly. Communities with fewer resources are more likely to be located in high-exposure zones, which compounds risk. In a recent analysis, even after accounting for income and education, neighborhood context itself remained an independent driver of outcomes. These insights remind us that the clinic is only one piece of the puzzle; lung health is shaped long before a patient arrives in front of us.

Sex and gender further shape trajectories. Across registries and post-hoc analyses of Scleroderma Lung Studies I and II, men present with more severe lung involvement, experience faster forced vital capacity (FVC) decline, and have worse long-term outcomes, whereas women, on average, show greater FVC gains with cyclophosphamide or mycophenolate; adverse-event profiles also differ by sex. Standard therapies improve lung function in both sexes, but they do not fully eliminate these differences; in SLS II, male sex remained associated with greater progression and higher mortality risk. The hopeful takeaway is practical: earlier recognition, equitable access to proven therapies, vigilant first-year monitoring with thoughtful follow-up, and sex-aware care can narrow gaps and improve outcomes.

What all of this tells us is that disparities in ILD are real. They are multifaceted, and clinically significant, but they are not insurmountable. Patients may enter the journey at different starting lines, shaped by ancestry, environment, or gender, yet their destination can be profoundly influenced by how we as a medical community respond. “Equity in ILD care is not just about the therapies we prescribe—it’s about the systems we build to deliver them.” As new antifibrotic treatments, genetic insights, and precision medicine strategies emerge, the stakes are higher than ever. We must ensure that the benefits of scientific progress are not unevenly distributed. By recognizing earlier onset in some groups, mitigating environmental risks where patients live, and guaranteeing access to proven therapies across sex and gender, we have the tools to bend the trajectory of disease. The challenge (- and the opportunity we now have) is to use them well.

If you are a health practitioner, you may Login/Register to comment.

Due to the nature of these comment forums, only health practitioners are allowed to comment at this time.