Shifting the Management Paradigm for SLE and Lupus Nephritis Save

The paradigm for treating patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is rapidly shifting and our patients will surely benefit with improved outcomes.

For many years, we used corticosteroids like water. They work fast and keep SLE disease under control, but we used them for too long and doses were too high. We had the ongoing and nagging question of whether it was the corticosteroids or the SLE disease activity itself, most often occurring in parallel, that were the cause of so much irreversible organ damage, e.g., atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease. But now, with effective immunosuppressants and biologics available, we can clearly see that it was the corticosteroids that greatly contributed to organ damage, which has a fast and early onset. Thus, a large part of the paradigm shift is to rapidly taper corticosteroids and start effective immunosuppressants, including biologics, as soon as possible.

New guidelines for the management of SLE and lupus nephritis are coming out fast and furiously, but will need constant updating.

The most recent 2023 European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) guidelines for SLE and lupus nephritis, the just released online 2024 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) lupus nephritis guidelines, and the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) and guidelines all point to more rapid and aggressive use of disease modifying therapies and biologics with rapid tapering of steroids1-3. Moreover, management guidelines have been proposed to be “living guidelines” and will need frequent revision and updates. This is a good problem to have as it reflects the acceleration of new treatments coming to market and new evidence about how to use them to best manage SLE.

The pipeline of new therapeutics for SLE is full and there is intense interest in cracking the code for SLE pathogenesis.

The REGENCY phase 3 trial of obinutuzumab, a more powerful B cell depletion agent than rituximab, for lupus nephritis was recently been published in New England Journal of Medicine and it is anticipated that it will become a first line agent in the treatment of lupus nephritis, pending FDA approval sometime later this year4. The Tyk-2 inhibitor deucravacitinib also looks very good in phase 2 trials and may be on its way to approval5. Jak inhibitors may also be coming to SLE, although there is some ongoing debate about possible increased thrombotic and cardiovascular risk6,7. And that is not even to mention the extreme excitement and interest in chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell directed therapies, and newer bispecific or “off the shelf” constructs, in potentially “curing SLE”8. There is also buzz about emulated comparative effectiveness trials in observational data, and even head-to-head and drug combination randomized trials, and cessation trials, to discover how long medications need to be continued once started, which we really still do not know.

We should recall, though, that SLE is one of the most heterogeneous diseases in its manifestations and severity. While there is undertreatment, there is also over- and inappropriate treatment. Many patients have just mild disease with some rashes, and photosensitivity, arthralgias or arthritis, and fatigue. They are usually well controlled with hydroxychloroquine, and possibly methotrexate or belimumab.

The challenge now is to develop precision and personalized treatment paradigms, as mentioned in the EULAR guidelines, as one size will not fit all3. If we can predict from initial presentation which patients are likely to have which kinds of SLE (e.g. mild, moderate, life-threateningly severe), and the medications to which they are most likely to respond (based on biomarkers and the biologic pathways involved), we would simultaneously be able to limit corticosteroids and provide each person with the truly tailored and optimal SLE medication ideally suited to their own disease. This is an extremely attractive idea for both patients and their healthcare providers.

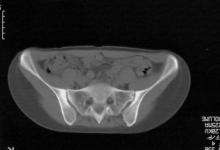

Figure 1. Recommendations for the treatment of class III, IV with or without class V lupus nephritis. Source: 2024 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) Guideline for the Screening, Treatment, and Management of Lupus Nephritis

References

1. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes Lupus Nephritis Work G. KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the management of LUPUS NEPHRITIS. Kidney Int. 2024;105(1S):S1-S69.

2. 2024 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) Guideline for the Screening MaToLN. https://assets.contentstack.io/v3/assets/bltee37abb6b278ab2c/bltdeb3e67a69a4528a/lupus-guideline-lupus-nephritis-2024.pdf. Published 2025. Accessed May 7, 2025.

3. Fanouriakis A, Kostopoulou M, Andersen J, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of systemic lupus erythematosus: 2023 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2024;83(1):15-29.

4. Furie RA, Rovin BH, Garg JP, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Obinutuzumab in Active Lupus Nephritis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2025.

5. Morand E, Pike M, Merrill JT, et al. Deucravacitinib, a tyrosine kinase 2 inhibitor, in systemic lupus erythematosus: a phase II, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Arthritis & Rheumatology. 2023;75(2):242-252.

6. Hasni SA, Gupta S, Davis M, et al. Phase 1 double-blind randomized safety trial of the Janus kinase inhibitor tofacitinib in systemic lupus erythematosus. Nature communications. 2021;12(1):3391.

7. Merrill JT, Tanaka Y, D'Cruz D, et al. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib or elsubrutinib alone or in combination for patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: A phase 2 randomized controlled trial. Arthritis & Rheumatology. 2024;76(10):1518-1529.

8. Mullard A. CAR T cell therapies raise hopes-and questions-for lupus and autoimmune disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2023;22(11):859-861.

If you are a health practitioner, you may Login/Register to comment.

Due to the nature of these comment forums, only health practitioners are allowed to comment at this time.