An educational review of Rheumatology - evaluation, testing, diagnosis and treatment of common inflammatory and autoimmune disorders. Please add your comments and discussion in the comment area below.

Advanced Practice Rheum: Difficult to Treat Rheumatoid Arthritis Save

Other videos in the Advanced Practice Rheum Series:

- Evaluation of Rheumatic Complaints

- Rheumatoid & Inflammation Testing

- Antinuclear Autoantibodies (ANA)

- Methotrexate

TRANSCRIPT:

Editor’s note: This transcript has been prepared from the original recording and may include transcription inaccuracies. Please rely on the video for the most complete and accurate information. Visit our Mission APP: Partners in Care site for more APP-focused articles and videos.

In this Advanced Practice Rheumatology review, we're going to discuss difficult to treat RA, also called D2T-RA or refractory RA. We'll go over the definition of D2T-RA as established by EULAR, and I will throw in some other scenarios in RA management that are difficult to treat and should be considered as such. Hence, I'm going to expand D2T-RA to include recurrent rheumatoid arthritis flares, seronegative rheumatoid arthritis, and complications of RA, especially interstitial lung disease (ILD) associated with RA.

Flares in RA are common and occur in 30 to 60% of patients. ALERT: there are way too many studies showing flares most frequently happen when you withdraw therapy – I don't know why we do this. I don't do this.

Treating RA is difficult, taking time and effort with trial and error, trying to find the right drug or combination of drugs to control a chronic systemic inflammatory disorder that has deadly complications. And then, once you achieve a great response, talk begins (by the patient and you) about wanting to stop or taper therapy. This is not a good idea at all. If you taper DMARD or biologic therapy, flares are likely and if you stop DMARD or biologic therapy, flares are certain. And there are significant consequences to RA flares. One flare, not so bad, you can manage it with temporary medicines, but repeated flares will have worse 12 month outcomes in the things that matter most to the patient.

With repeated flares there will be more x-ray progression and a higher cardiovascular risk. And there are certainly economic consequences to flares with being out of work, more healthcare, utilization, more comorbidity management.

How do you manage flares? The best way to manage flares is to avoid a flare. Keep them well controlled. Keep them on stable therapy. The goal is to be boring and stable. If therapy is working, let's not change a thing. Just follow - Don't taper, don't stop DMARDs or biologics. The goal is remission or low disease activity state.

I think you should be documenting the flares. Often patients will call and say, "I'm flaring," and they'll be managed over the phone without ever being seen or without any kind of metric being used to document the flare. You can use remote assessment tools or telemedicine or surveys over the phone to come up with a RAPID3 or PAS score. You could also bring them in and do a joint count and a CDAI or whatever metric that you use to follow patients in your clinic.

Treatments for flares are thankfully simple, cheap, and effective, but they do have toxicities. The problem is that many are really not that effective. Time (waiting) and rest are effective for most flares. You should always recommend rest, cutting back on activities, cutting back on exercise, stop doing the thing that caused the flare. Those would be smart.

What are your treatment options for flares? Analgesics, acetaminophen, tramadol, weak narcotics, and NSAIDs. These have been largely shown to not work or have minimal effect, but mainly impose risks. I prefer to use acetaminophen. Most people don't use acetaminophen correctly, using short acting, 325, 500 mg acetaminophen instead of using the right dosing of long acting acetaminophen of 650 mg tabs – 2-3 tabs twice a day during flares with or without a low dose NSAID, or possibly a low dose of prednisone (2.5-5 mg/day temporarily)..

But you worry about toxicity, do you not? Especially with NSAIDs in people who shouldn't be taking non-steroidals.

What about steroids. Everybody's got their formula for steroid use; come in for a steroid shot or take a Medrol dose pack or take 10 mg a day for three days or start out with 15 mg a day for two days, 10 mg a day for three days, five mg a day for four. This is crazy as none are evidenced based. Yet, what we do seems to work. Is it the steroids or time and rest?

Daily steroids should be used in the lowest possible dose, anywhere from 2.5 - 10 mg daily is preferred, lasting 3 - 7 days, with a firm stop date. You don't want to start steroids that you can't stop.

Why not consider RA flare management as you do gout. Gout patients who have 2-3 or more flares in a year are candidates for prevention and chronic urate-lowering therapy. A rheumatoid patient who has three or more flares is also a candidate for a change in DMARD to either a biologic or targeted synthetic therapy. With repeated flares we should consider D2T-RA management strategies.

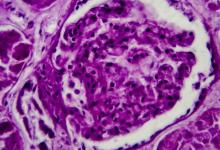

Let's move on and talk about ILD. RA patients, especially seropositive patients, are at higher risk for ILD. Remember the “3 S Rule”: sex (being male), seropositivity and smoking. If you have those three, you have a significant, seven fold higher odds of developing usual interstitial pneumonitis (UIP) ILD. ILD carries a significantly higher (3 fold) risk of serious hospitalizable infections. It's also associated with a 5 - 5 fold higher risk of mortality in the next 10 years. ACR put out ILD guidelines a few years ago.

The problem with guidelines and treatment of ILD is, it's all expert opinion, as the best evidence is lacking. First line therapy, the ACR guideline suggests either mycophenolate, azathioprine or rituximab. When that fails,next you can consider using cyclophosphamide and maybe short-term steroids. In 2025, EULAR updated its guidelines, basically saying that not all RA patients with ILD have to be treated, but they should be assessed and monitored. And if they RA-ILD risk factors, you can use drugs that will help in ILD, as well as in their RA; including abatacept, rituximab, JAK inhibitors, tocilizumab, steroids, mycophenolate, azathioprine. If they start to develop more severe or progressive ILD, they need a combination of immunosuppressives. If they develop progressive pulmonary fibrosis, EULAR says you can use the antifibrotic drugs nintedanib or combinations of nintedanib with immunosuppressives. And then lastly, UIP pattern ILD should get pirfenidone.

Let's end with D2TRA, defined by EULAR as having RA activity that's unacceptable both patient and doctor, and having failed two or three biologic or targeted synthetics DMARDs (of different mechanism of action). The EULAR definition of D2T-RA requires > 2 b/tsDMARD failures. Others use the term polyrefractory RA that requires > 3 b/tsDMARD failures. People who meet the D2T-RA definition are usually younger, have active synovitis, seropositivity, Xray erosions and they may be smokers or obese, with fibromyalgia or depression.

The important thing here is to recognize that half of the D2TRAs are driven by RA inflammation and may need further immunosuppressive or biologic therapy. The other half of D2T-RA patients probably have fibromyalgia and functional disease. We can divide D2T-RA into NIRRA or PIRRA. NIRRA stands for non-inflammatory refractory RA, that's usually the fibromyalgia-like half of D2T-RA. And PIRRA stands for persistent inflammatory refractory RA. You can distinguish NIRRA from PIRRA on clinical grounds.

PIRRA patients have elevated ESR or CRP levels,swollen joints, ultrasound evidence of synovitis and disease activity reflected in a high DAS28-CRP. Such patients may need more aggressive RA specific therapies. Without these features you should consider NIRRA, these patients are often obese with many tender joints, but no swollen joints. They usually meet criteria for fibromyalgia, with poor sleep and related disorders (IBS, migraine, depression, etc). NIRRAs are non-inflammatory, and they need to be treated differently than PIRRA patients

If you think about it, the PIRRAs are people that have lots of joints, extraarticular manifestations, acute phase reactants, seropositivity, erosion, and shared epitope. The NIRRA are people who are non-adherent, have bad behaviors, wrong diagnoses, coexistent functional disease, depression, anxiety, etc.

One more important consideration about RA treatment and D2T-RA.

An RA patient who fails first line therapy or first line combination, is subsequently less likely to respond to your next choices. That's the bad news. Failure begets more failure, especially in those who become D2T-RA. Hence, be aggressive and get it right the first time, and if you have to be be aggressive with your second regimen and get that right. Otherwise, when you're cycling through therapies with lower and lower expectations.

You have lots of drugs to choose from, but how should you choose when the patient has D2T-RA? My advice is don’t automatically just consider the drugs. Instead you should consider if your D2T-RA is due to either the wrong diagnosis, wrong patient, wrong doctor and then possibly the wrong drug.

For wrong diagnoses, I'm thinking about seronegative RA patients and those who have been misdiagnosed as RA. It could also be that you're mistaking flares of fibromyalgia or depression and poor sleep, when you or the patient thinks symptoms and failure is from RA, when its not.

Some patient characteristics make them harder to manage and they end up as D2T-RA. You should identify bad traits that portend that the patient may not do well. These bad traits includes those who are non-compliant, patients who think they're doomed to fail, those bad at managing their disease, and often includes poor sleepers, those with anxiety, depression, or magical thinkers.

Recognize that depression is a major problem in rheumatic disease patients. In RA, it's seen in up to 50% of patients. There's a bidirectional relationship between having depression and RA risk. Bad news: in the DANBIO Danish registry RA patients with depression had a threefold higher risk of mortality.

Why worry about seronegative RA? Seronegative RA could be an alternative diagnosis - it could be palandromic rheumatism, polymyalgia rheumatica, undifferentiated arthritis, inflammatory arthritis, CPPD, Whipples, etc. .

With seronegative arthritis patients each clinic visit is your opportunity to rediagnose them correctly or consider other diagnoses. In studies of patients with seronegative RA that were followed for many years, as many as two thirds of them changed diagnoses to either PMR, psoriatic arthritis, spondyloarthritis, or even osteoarthritis.

The other unifying feature to misdiagnosed RA is that they have atypical presentations, longer time to make a diagnosis. They are more likely to fail multiple DMARDs, biologics and have DMARD toxicities. RA misdiagnoses often turn out to be tophaceous gout, psoriatic arthritis, erosive OA, enteropathic arthritis, calcium pyrophosphate, deposition (hemochromatosis or an endocrinopathy), early CTD,or PMR.

When it comes to treating PIRRA D2T-RA RA patients, with signs of inflammation, acute phase reactions, positive ultrasound, your next choice has got to be a smart choice. This is often dictated by the patient's history, comorbidities, things that they can take and not take.

When prescribing DMARDs in the face of comorbidity you should consider this slide source from RheumNow.com. For example, if they have diverticulitis, you shouldn't be using prednisone, JAK inhibitors or IL-6 drugs. You can use anything else. If they have tuberculosis or mycobacterial concern, you should not be using any TNF inhibitors or prednisone, but it is safe to use IL-1 inhibitors, rituximab, abatacept, IL-6 inhibitors, IL-17 inhibitors, JAK inhibitors, etc. Again, sometimes comorbidities and toxicities help you to back into what your next best choice should be.

Lastly, I'll suggest 7 drugs that I've used to manage RA when FDA approved drugs failed. This includes some RA FDA approved agents such as anakinra, intramuscular gold, cyclophosphamide or cyclosporine. I have occasionally used with some success these “off-label” drugs, including mycophenolate, apremilast, or IL-17 inhibitors, especially in seronegative patients.

Anyway, this is the approach to managing patients with difficult to treat RA.

Watch for more advanced practice rheumatology.

If you are a health practitioner, you may Login/Register to comment.

Due to the nature of these comment forums, only health practitioners are allowed to comment at this time.