Non-Tuberculous Mycobacterial Infections - Diagnosis and Management for the Rheumatologist Save

Infections due to Non-Tuberculous Mycobacteria (NTM) are some of the most frequently reported opportunistic infections in the setting of biologic therapy. These organisms are ubiquitous in water (including drinking water) and soil. There are 178 species of NTM, with only a minority being clinically relevant.

The vast majority of NTM lung disease is caused by M. avium complex (MAC), followed less frequently by M. kansasii, M. abscessus, M. xenopi, or M. malmoense. Pulmonary disease is acquired from the environment, almost exclusively in those with underlying lung disease, and it is insidious and indolent with long delays in diagnoses common.

Approximately 50% of individuals will require multi-antibiotic therapy for long durations (18-24 months) to either cure or suppress the disease.

Immunosuppression increases the risk of disease acquisition and progression. Extrapulmonary disease is less common, although is more likely in immunosuppressed patients and more likely to require long-term intravenous therapy with multiple antibiotics.

When should I suspect my patient has NTM?

- Most NTM infections are pulmonary, but similar to tuberculosis, both extrapulmonary and disseminated manifestations are more common in immunosuppressed patients. Outside the setting of cystic fibrosis or other rare inherited chronic lung diseases, pulmonary disease occurs almost exclusively above the age of 40 years, with a female predominance (60-65%). Tall and thin individuals with scoliosis or pectus defects are at higher risk (this morphotype is associated with bronchiectasis). Rheumatoid lung, bronchiectasis, COPD, or other forms of chronic underlying lung disease are risk factors. Patients using corticosteroids (oral or inhaled), TNF inhibitors, and potentially other biologics are at increased risk. These same immunosuppressive agents increase the risk of NTM extrapulmonary infections (e.g. skin and soft tissue), particularly the long-term use of corticosteroids at higher doses (e.g. 15mg and above). While localized cutaneous NTM infections and pulmonary disease can occur in healthy hosts, disseminated NTM disease does not occur in fully immunocompetent persons.

NTM Screening, disease presentation, and diagnosis

- There are no accepted screening methods for pulmonary NTM. For patients in whom disease is suspected (based on symptoms or CXR findings), then a non-contrast chest CT should be obtained along with respiratory specimens for AFB culture. Patients must meet American Thoracic Society disease criteria to be diagnosed---these include (1) radiographic evidence of disease (tree-bud infiltrate, nodules, cavity) (2) one BAL or two sputum cultures positive for NTM and (3) symptoms compatible with disease (fatigue, cough, dyspnea, fever, or weight loss).

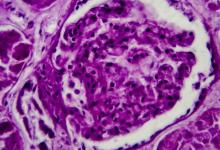

- Extrapulmonary NTM disease most frequently manifests as skin and soft tissue, disseminated, or lymph node infection. Skin lesions are generally nodular and frequently purple or dark in color. Biopsy of lesions for AFB culture, stain, molecular examination, and histopathology are essential to make a diagnosis.

Treatment of pulmonary NTM and outcomes

- The vast majority of pulmonary NTM is caused by MAC. Patients generally use a macrolide, together with rifamycin and ethambutol for 18-24 months in either daily or thrice weekly fashion. Intravenous Amikacin is frequently added for the first 2 months if cavitary disease is present. While respiratory culture conversion is common, relapse or re-infection from the environment is also common after therapy stop (approximately 50% in 3 years after therapy stop). Patients with cavitary disease are more likely to rapidly progress, have worsened lung function, and higher mortality. Treatment of other species is less well defined, but typically involves a macrolide and other agents as per antibiotic susceptibility testing results. Macrolide monotherapy should never be attempted. Rheumatologists should refer patients with NTM disease for treatment by a pulmonary or infectious disease consultant with experience in these infections

Treatment of extra-pulmonary NTM and outcomes

- While MAC is also the most common cause of extrapulmonary infections, the rapidly growing mycobacterium M. chelonae, M. abscessus, and M. fortuitum are also important causes of such infections. Therapy for MAC is similar to that described above for pulmonary MAC. Therapy for these rapid growers, however, frequently involves 1-2 Intravenous therapies in addition to 1- 2 oral antibiotics according to antibiotic susceptibility testing. Intravenous therapy should be employed for 2-4 months depending upon the extent of oral options available, and overall lengths of therapy frequently involve 6-12 months or longer. Frequently therapies such as amikacin, tigecycline, imipenem, or cefoxitin are used in combination with macrolides and fluoroquinolones. These infections are frequently highly drug resistant with limited oral options. Reversing or mitigating immunosuppression is key to successful therapy.

How to manage DMARDs in those with pulmonary or extrapulmonary NTM

- The spectrum of pulmonary NTM disease varies according to pathogen and host factors. Immunosuppression increases the risk of disease, although the behavior of disease in patients while using DMARDs is variable. Case series of antibiotic-treated NTM patients suggest some patients can tolerate concurrent biologic therapy while others do not. In general, as with other active infections, prednisone and biologic use should be limited or avoided if possible. There is no data suggesting that non-biologic DMARDs are associated with increased NTM risk or progression, and their use for disease management is favored in such patients. For extrapulmonary disease, these same principles apply and biologics should be stopped and prednisone weaned or eliminated if possible. In all cases, collaborate closely with the infectious disease or pulmonary specialist treating NTM as both the burden of infection and the need for rheumatic disease treatment are a moving target.

Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al; An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. ATS Mycobacterial Diseases Subcommittee; American Thoracic Society; Infectious Disease Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007 Feb 15;175(4):367-416.

If you are a health practitioner, you may Login/Register to comment.

Due to the nature of these comment forums, only health practitioners are allowed to comment at this time.