Prescribing Rules Save

If you are responsible for the outcome and welfare of patients – you need prescribing rules.

If you are supervising others or responsible for the training of those learning rheumatology – you need prescribing rules.

Rules for prescriptive behaviors hold the purpose of optimizing health outcomes, promoting safety, avoiding unnecessary risks or costs and providing consistency of care across all providers and patients. In no particular order:

- Use your best drug first – this is an edict from the great Fred Wolfe who wrote about the approach to RA therapy in the 1990s. This was right around the time when methotrexate (MTX) was becoming the cornerstone of RA therapy. While the rule seems obvious, it is a departure from the prior rule of use your safest drug first.

- Use best dose first – Start with optimal doses unless there is evidence that “start low, go slow” with increases in dosing is truly safer and superior. In my opinion, the start low, go slow only applies to penicillamine and apremilast. I believe the starting dose of MTX should be 15 mg weekly unless there is a reason to start lower. Best dose first gives you a more rapid answer to the question, “will this drug work in this patient”.

- Zero sum additions – Polypharmacy is worrisome, dangerous and rampant, especially in the elderly and patients with chronic disorders like RA, lupus, etc. To avoid this problem, one approach would require that for each new prescription, you need to stop or decrease one or two old prescriptions. (And while you’re at it, review their OTC and vitamins to stop as many of those as possible.)

- "Just right" requires over-treatment - Just as “best drug” and “best dose” intend to optimize and quicken eventual outcomes, the acceptance of overtreatment as an approach is often necessary at the outset or when a disease is out of control. Overtreatment is indicated and supported when: a) the slow addition of past treatments has resulted in failure; b) the patient cannot afford a 3-12 month wait to achieve a response; c) you have a plan to reduce risk and monitor for safety; and d) the risks associated with severely uncontrolled disease outweighs the additive low risk of each intervention. Once overtreatment (e.g., NSAID, low dose prednisone, MTX +/- a TNF inhibitor in someone with a DAS28 of 6.5, 12 swollen joints and inability to work) has been successful, paring down to the most effective agent(s) allows continued benefit and lower risk.

- Quality of life trumps remission – If treating patients, you have to first alleviate pain and second focus on quality of life and what is important to them. This is not to say that a HAQ=0 is preferable to a DAS28 of 2.5. It means you need to first understand each person’s goals and ideal outcomes. While T2T (treat-to-target) strategies and research have shown considerable advantages, the evidence for T2T success in daily practice is limited. Why is T2T strongly supported by the Pharma industry? Because, in addition to objective optimal outcomes, it does promote rapid drug switches, thereby increasing the odds of getting around to the new drug on the formulary.

- Patient medication rules – Regardless of the drug, each patient needs more than a prescription from you. They need rules specific to that drug and you the prescriber. I tell my patients the following – a) No one changes or stops my prescribed medications but me (the prescriber); b) Do not take half the dose I prescribed because your think it’s safer or the right thing to do; c) This drug requires that you be seen by me every __ weeks/months and have laboratory tests every __ weeks/months; d) Do not change your medication use based on something seen on TV, the internet or overheard at the hairdresser; e) Do not guess when it comes to medication – call my office if you have a question, a concern or a worry. You could print this and post in each exam room. Be very clear that you take seriously your responsibility for each and every prescription you write for.

- Med lists and drug reviews – every patient should be given an updated medication list at every visit. Every patient must bring their medication list OR a bag full of all medications to each visit. Patients who are poorly communicative, elderly, noncompliant or non-English speaking are REQUIRED to bring all pill bottles to each visit and all doctor visits for review and instruction. Have a specific handout for each drug – what it’s for, how/when to take, what are the reasonable expected side effects, when to stop, what to do if you miss a dose, etc.

- Always know the cost of the drug you prescribe – Always give patients instructions that include the rough cost, whether covered by insurance, Medicare, if it comes as a generic or has a cheaper alternative. Ask patients who pays for their drugs and if they have a problem paying for drugs. With this in mind you become part of their solution rather than adding to their problems.

- Forewarned is fore-armed – Alert the patient as to the pitfalls of this drugs use; meaning what person, factors, magical thinking or public information going to undermine patient trust in you and their compliance with your prescribed therapy.

- Strong opioids requite a strongly written pain contract - This needs to be presented, discussed and signed by both you and the patient (download here), with copies going to the patient and the patients chart.

Pitfalls in Prescribing

The following “pitfalls” were written by C. Michael Stein, MD a rheumatologist at Vanderbilt Medical School and co-author for our online rheumatology textbook “RheumaKnowledgy”. I believe these sage “rules” compliment those above. Thanks to Mike!

The clinician should be careful to avoid the following common mistakes in prescribing:

- Prescribing a drug when no drug is needed. Alternative, nondrug methods of symptom control may be the appropriate intervention.

- Prescribing no drug when a drug is indicated. Therapeutic nihilism or therapeutic ignorance may deny patients effective and necessary treatment.

- Prescribing a poorly chosen drug for the disease. A drug that is ineffective, expensive, and potentially harmful (e.g., methotrexate to treat gout) should be avoided. Also common is the mistake of choosing a drug that has similar efficacy but is more expensive or has more side effects than the treatment of choice.

- Prescribing a poorly chosen drug for the patient. The patient is a major determinant of rational prescribing. Children, the elderly, pregnant or lactating women, patients with renal or liver disease, and patients receiving other drugs all require special consideration.

- Prescribing a drug incorrectly. A correct drug for the patient and the illness may be chosen, but the drug may be prescribed incorrectly. The dose, dose interval, duration of therapy, and route of administration must be considered. An example of this is the prolonged use of high-dose corticosteroids in RA (which should be tapered as soon as possible). Last, the prescriber should be familiar with the drug’s indications, contraindications, proper dosing, common and uncommon side effects, precautions, drug interactions, mechanism(s) of action, and the drug’s cost to the patient.

- Not providing a patient with essential information. This is particularly important in long-term therapy with potentially dangerous drugs (e.g., cyclophosphamide) and drugs that must be taken in a particular way (e.g., alendronate).

- Failing to monitor appropriately. Many drugs are potentially toxic, and appropriate long-term monitoring is essential. Assessing the patient’s clinical response and modifying therapy appropriately, in addition to laboratory monitoring, is important.

- Polypharmacy. Many patients require long-term therapy with multiple drugs. Nonetheless, the requirement for ongoing medications should be thoughtfully reviewed.

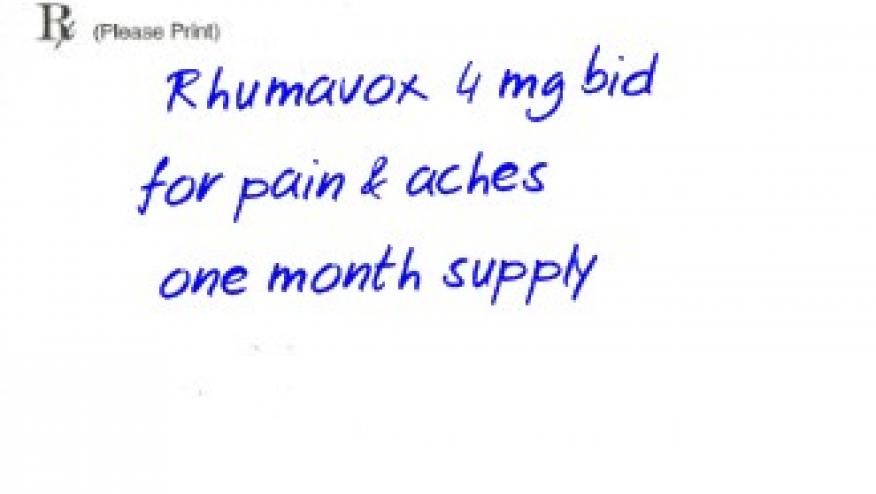

- Illegibility. Tragedies have occurred because of illegibility. Printing is preferable. Avoid abbreviations (e.g., MTX for methotrexate) when prescribing. Electronically generated prescriptions may lessen prescribing errors by both physicians and pharmacists.

If you are a health practitioner, you may Login/Register to comment.

Due to the nature of these comment forums, only health practitioners are allowed to comment at this time.