Study Backs CellCept for ILD in Scleroderma Save

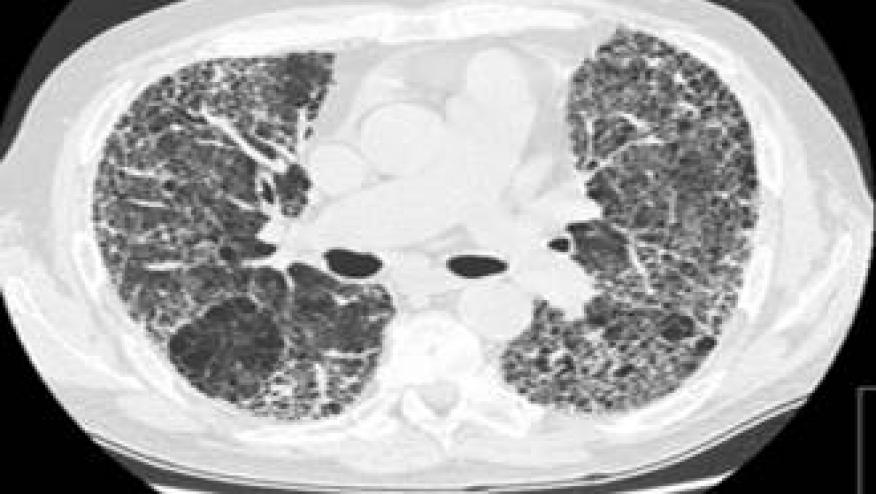

MONTREAL -- An immunosuppressive drug was as effective as a standard agent for interstitial lung disease (ILD) associated with scleroderma, a researcher said.

But mycophenolate (CellCept)was better tolerated than the old standby, the oral alkylating agent cyclophosphamide, according to Donald Tashkin, MD, of the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California Los Angeles.

The result wasn't entirely surprising because physicians have been voting with their prescription pads in favor of mycophenolate for several years, Tashkin reported here at the annual CHEST meeting.

Doctors "have already figured out" that mycophenolate has some attractive features, he said after his late-breaking presentation.

But the grassroots movement toward mycophenolate has been based on small uncontrolled studies, without a gold standard trial, he said. To help fill that gap, he and colleagues conducted the Scleroderma Lung Study II, a randomized double-blind trial comparing the two medications.

It comes a decade after the Scleroderma Lung Study, also led by Tashkin, which compared cyclophosphamide to placebo in patients with ILD subsequent to scleroderma. That study found that a year of cyclophosphamide led to modest but significant improvements in lung function and dyspnea, but the benefits were lost after 2 years.

The drug also has significant toxicity and use for more than a year increases the risk of cancer, he noted. So doctors, knowing that ILD is now the leading cause of death in scleroderma, looked around for a better option and many settled on mycophenolate.

To help support or challenge those choices, Tashkin and colleagues enrolled 142 scleroderma ILD patients in 14 sites and randomly assigned them to 2 years of mycophenolate or a year of cyclophosphamide followed by placebo for a year.

The hypothesis was that the course of lung function, as measured by the forced vital capacity percentage of predicted value (%FVC), would respond better to mycophenolate, and that the drug would also prove less toxic.

Patients were encouraged to continue to contribute data on their lung function and other measures even if they stopped taking their study drug, he noted, and after 2 years the investigators had data on 53 patients in the cyclophosphamide arm (including 16 who were off the drug), and the same number in the mycophenolate arm (including four who were off the drug).

At the end of the trial, patients in each arm had a significant improvement in %FVC compared with baseline, but the difference between the drugs was not significant.

On the other hand, both drugs led to declines in the diffusing capacity of the lung (%DLCO) that did not reach significance in either arm compared with baseline, but were significantly different compared with each other.

More patients stopped study drug in the cyclophosphamide arm -- 36 of 73 versus 20 of 69 -- and the time to stopping drug was significantly shorter (atP=0.019) among cyclophosphamide patients, Tashkin said.

Sixteen patients died during the trial -- 11 taking cyclophosphamide and five on mycophenolate, but the difference was not significant. All but one of the deaths were attributed to the underlying scleroderma.

About the same number of serious adverse events occurred in each arm, but significantly more in the cyclophosphamide arm were attributed to the drug -- eight versus three, Tashkin reported. There was also significantly less leukopenia and thrombocytopenia in the mycophenolate arm, he said.

The findings support the use of mycophenolate, Tashkin, but he toldMedPage Todayit would be "entirely reasonable" to start a patient on cyclophosphamide if it was well tolerated and then switch after a year for mycophenolate maintenance.

The study is essentially looking for ways to improve therapy for ILD in scleroderma, commented Thomas Fuhrman, MD, of the Bay Pines VA Healthcare System, near St. Petersburg, Fla.

And it appears to give support to doctors already using the drug, he toldMedPage Today.

The next step, he said, might be to try to find drugs that could be added to mycophenolate -- or perhaps to replace it -- to improve outcomes even more.

This study was supported by the NIH. Roche Pharmaceuticals provided mycophenolate for free for the study. Taskin disclosed no relevant relationships with industry. Furhman disclosed no relevant relationships with industry.

This article is brought to our readers by our friends at MedPage Today. It was originally published on October 28, 2015.

If you are a health practitioner, you may Login/Register to comment.

Due to the nature of these comment forums, only health practitioners are allowed to comment at this time.