The path to new technologies in rheumatology must be beset with caution Save

Sometimes it feels like we live in an antiquated bubble. We examine from the right side of the patient’s bed and we use Latin abbreviations to give critical instructions about our medicines, for no strong reason apart from the reason that we hav always done it that way.

It served our rheumatological forefathers well, and as the rightful torchbearers of the legacy of Osler and Heberden, we look at our whole craft built around this and see no good reason to dispose of this. Indeed, even though others from the outside probably think it is quaint that our professional domain is built in such a way, it reminds us of where we come from and how we have approached progress. We see the value in technological progress, but also that of our established approach and the implied caution that accompanies it - because our patients expect reliability. The authority that we command is dependent on an adequate level of certainty in what we say. Are we doctors? Yes, we certainly are.

As we have incorporated technology into our workflows, and consequently saved lives and suffering, we have balanced our excitement about progress with proof that incremental advances can truly deliver benefit. We are required to by legislative bodies, but really we are bound by our moral obligation.

We know this at our heart, but it is easy to let promise carry our caution away - and while most of the time such advances come in a vetted package, which we can consume without concern, conference abstracts come raw. This is the necessary ingredient to a platform which allows for bold ideas and innovation, but for that reason it is not such a curated space. It is not quite as unregulated as the lay media, which in turn is not quite as unregulated as the darker corners of social media, but it behoves us to apply the necessary filters to contextualise the excitement, and realise what is to come.

At EULAR 2024, we saw the usual mix of bright, raw ideas on the poster floor emblematic of this paradigm. Who doesn’t want a breath test that could make a reasonable diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis (POS0652)? A needle-free, accessible test that would need little expertise to undertake and which could direct patients more quickly to the diagnosis, further investigation, and treatment they need. We of course may never see this in practice, but hearing about this is the excitement of the poster floor.

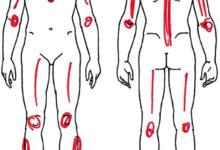

One of the more conceptually promising ideas is using computer vision to assess disease activity through hand movements (POS0607). The promise is easy to see: during telehealth, in the absence of being able to examine joints, we could take vision of hand movements and then assess them, then that could make telehealth a far more complete assessment and mean that it is more appropriate on a wider scale. Additionally, if an app could guide hand movement and then facilitate assessment autonomously outside of a clinician visit, disease activity could be tracked more exactly, adjustments in therapy could happen more frequently, and disease control could be far tighter.

It is easy to let this kind of promise seduce us, and to get ahead of ourselves. Especially when we see technology influencing other parts of our lives, it’s easy to become entranced by the hope. We have to remember, however, that inaccurate tools bring real risk of real harm, and that appropriate caution is mandatory, both figuratively and literally.

What is required?

Well even if this technical tool has a true clinical place, and can deliver meaningful performance, these tools need validation, in both research and real world settings, and consideration about clinical implementation and unintended consequences, including bias and clinician overreliance. Before we subject these algorithms to the swings and arrows of everyday clinical life, where people’s health is at stake, we have to think of the gap between an exciting conference abstract and consequential reality.

Thankfully I have confidence the researchers of the mentioned abstracts will undergo these processes in due course, but we should not presume that these technologies will be ready for public consumption soon, despite any obvious need and the benefit a successful tool could deliver.

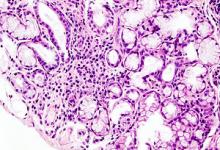

When I was a fellow I heard about an abstract on thermography in diagnosing inflammatory arthritis, and the details seemed interesting. I was determined to try it in practice and hoped it could help with diagnosing polymyalgia rheumatica, and I wouldn’t stop talking about it. My mentor decided to indulge me and, one Saturday morning, we went to the shop where the bemused sales manager let us try out the recommended device. When we went to try it out, it was so obviously useless for the job, much to my dismay. My mentor told me that, earlier that morning, his wife has asked him why he was bothering with this endeavour, and he told her it was so that I could learn. We all need that kind of appreciation of the limits of enthusiastic adoption, every now and then.

Join The Discussion

Hello Dr. Cush from Dubai !I believe artificial intelligence is progressing at a rapid rate and we are unaware. We evaluated a proprietary rule engine assisted by AI to make preliminary Rheum diagnosis and it was 98 percent accurate. Our abstract AB1488 at EULAR 2024 for publication only

If you are a health practitioner, you may Login/Register to comment.

Due to the nature of these comment forums, only health practitioners are allowed to comment at this time.