Congress Slams AbbVie Over Price Hikes, 'Frivolous' Patents Save

House lawmakers on both sides of the aisle pummeled AbbVie CEO Richard Gonzalez for raising the price of two widely used drugs and for the company's "legally questionable" tactics to head off competition from biosimilars, despite pulling in healthy profits.

Much of Tuesday's House Committee on Oversight and Reform hearing centered around two issues: the risks and benefits of Medicare price negotiation and potential abuse of the patent system.

Committee Chairwoman Carolyn Maloney (D-N.Y.) charged that Gonzalez and other AbbVie executives were "actively targeting" the U.S. for price increases while lowering prices in other countries.

AbbVie charges $77,000 for a year's supply of adalimumab (Humira), which is 470% more than what it charged when the drug was first launched in 2003. A single syringe of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blocking agent costs over $1,000 more in the U.S. compared to some other countries, including Canada, Japan, Korea, and the U.K.

"Humira is the highest grossing drug in the United States, due in large part to these horrendous price increases," Maloney said.

Additionally, she noted that AbbVie and partner Janssen charge $181,000 for a year's supply of ibrutinib (Imbruvica), a cancer treatment.

Maloney also charged that instead of investing in research and development for other new drugs, "significant portions" of the company's research budget were spent strategizing ways to suppress competition.

Blocking Competition

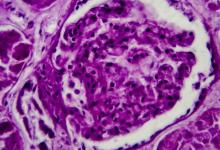

Internal documents found by the committee, in this its sixth report, showed that executives expected Humira, the company's top-selling drug -- used in rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune disorders -- to face competition from biosimilars as early as 2017, Maloney said.

"But AbbVie used legally questionable tactics to block lower-priced biosimilars from reaching American consumers until at least 2023," Maloney said.

Additionally, one reason drug companies, such as AbbVie, are able to raise prices so dramatically is due to "flaws and loopholes in our system," including a law that prevents the U.S. from negotiating drug prices, Maloney said.

She argued that the solution to the issue is to pass the Elijah E. Cummings Lower Drug Costs Now Act (H.R. 3) into law. The bill gives the HHS Secretary the power to negotiate drug prices in the Medicare program, "like the rest of the world does," Maloney said. (The bill is named after the late Chairman Elijah Cummings who Maloney credited with spearheading the committee's investigation into high drug prices nearly 2 years ago.)

Republicans, for the most part, were not ready to embrace drug price negotiation as a solution.

Threats to Innovation

Ranking Member James Comer (R-Ky) called the Democrats' bill, which has already passed in the House, a "massive government takeover."

Making H.R. 3 into law would result in "significantly fewer treatments and vaccines ... coming to market" and "destroy the very system that has made the United States the world leader in medical innovation," he said.

Comer instead lobbied for the "Lower Costs, More Cures Act," which he said would lower patients' out-of-pocket costs, while protecting innovation.

On the issue of intellectual property protections, Democrats view these as "the root of all evil," the ranking member said. Other witnesses suggested that eliminating such protection could create access problems and reduce innovation.

Comer acknowledged that some drug companies have abused the patent system, to extend their products' control of the market, "but many seek patents simply to protect their intellectual property so they can recoup their investments," he said.

For his part, Gonzalez argued that the real problem with drug prices is insurance coverage.

While the overall Medicare Part D program is "cost-effective," some Part D beneficiaries are forced to pay high out-of-pocket costs, because of the lack of a cap on drug spending, which exists in most other commercial insurance plans, Gonzalez said.

He also argued for "reapportion[ing]" the share of what patients pay in the catastrophic phase of the Part D benefit.

"No other prescription drug insurance program puts so much cost burden on the patient," he said.

Gonzalez also said that one in three Medicare patients on adalimumab seeks assistance and receives free medicine from AbbVie's patient assistance program.

Democrats, however, shared recorded videos from a handful of patients, from a senior on a fixed income to a college student, who were struggling to pay for AbbVie's drugs.

American Loyalty

Not every Republican Committee member was as conciliatory towards the primary witness as Comer was, particularly with regard to price hikes for American patients.

"How the hell can you explain [why] the prices overseas of the drugs you manufacture in America [and] develop in America are so much higher for American citizens and patients?" asked Rep. Clay Higgins (R-La.).

Gonzalez responded that outside of the U.S., socialized healthcare systems set prices and "ration care."

Higgins agreed with Gonzalez that "socialist policies" like price negotiation don't work. He said that prior to 1986, Europe had outpaced the U.S. in pharmaceutical research and development, and that progress was lost because of policy choices made there.

"But you're an American company, making American money, and your market is global. American citizens should benefit from your love and commitment to the country, wherein you live and work, good sir," Higgins said.

'Too Many Patents'

Higgins also pointed out that AbbVie had been accused of using its patent portfolio to delay biosimilars from coming to market.

As Rep. Ro Khanna (D-Calif.) noted that Humira's price fell by 80% when biosimilars were introduced in Europe, Gonzalez interjected that revenues fell by closer to 50%.

"Our point here is competition works. Correct?" Khanna said.

"That is correct," Gonzalez affirmed.

According to the written testimony of another witness, Tahir Amin, the co-founder and co-executive director for the Initiative for Medicines, Access, and Knowledge (I-MAK) and an attorney, AbbVie has applied for 257 patents for adalimumab, of which 130 were approved -- 90% of these were filed after the product was already brought to market. AbbVie similarly submitted 165 patent applications for ibrutinib, of which 88 have been granted, Amin noted.

These so-called patent thickets allow companies to maintain a monopoly on prices by preventing competitors from entering the market.

Higgins asked Gonzalez to explain the "legitimacy" of AbbVie's patents.

AbbVie received approval for patents focused on the dosage of the drug being used, which was already described in marketing materials, and for changes to the needle size of its products, other members noted.

Just as Gonzalez began to defend his company against claims that his patents were "frivolous," Higgins cut him off: "They're frivolous," Higgins said, AbbVie made "minute changes" to extend its hold on the market.

"Look, I'm no enemy of big business," Higgins said. "You have the right to earn your ... honest profit, but it's the question of whether or not it's an honest profit, sir, that I would extend."

Amin argued that the solution to the problem is to raise the bar on patent approval.

"Too many patents are granted that are too weak," he said.

Aaron Kesselheim, MD, JD, MPH, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School in Boston, agreed that patent offices need to raise the bar, so that only "clinically meaningful" patents are approved. To do that they need more time for review and more resources, he said.

Amin also suggested that the incentives and culture of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office needs to change. Patents that are granted provide revenue for the office, "and we need to create a financial incentive that actually works outside of that," he said.

Join The Discussion

This a good reason for for rheumatologists to separate themselves from industry attachments and to always beginning with nonbiological therapies first. This is one example how industry greed continues to grow with the help of our government. We are the patient’s physician and should continue to act like it. The patient does seek you out as an industry advocate, but as their advocate. Somewhere, some of us got lost in our ambitions.

If you are a health practitioner, you may Login/Register to comment.

Due to the nature of these comment forums, only health practitioners are allowed to comment at this time.