Intraarticular Steroids in OA Lowers Need for Pain Meds Save

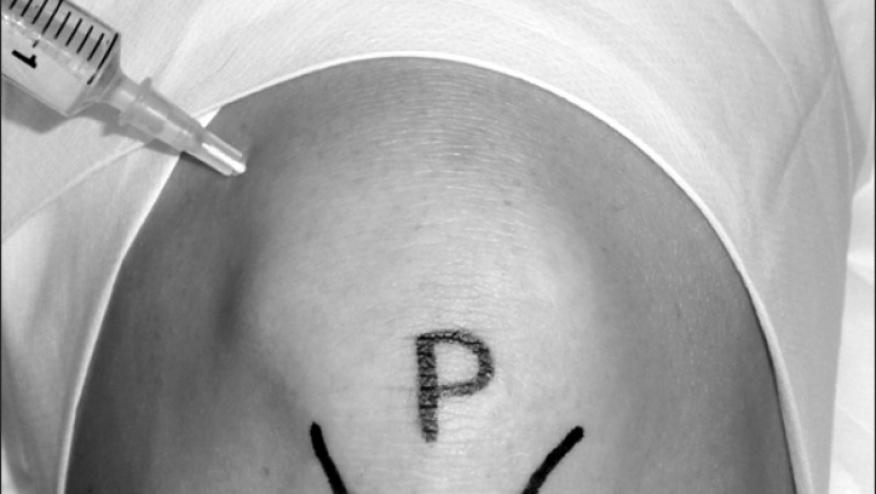

Is it possible that intra-articular corticosteroid injections for osteoarthritis might affect the use of opioids?

British patients with osteoarthritis (OA) who received intra-articular corticosteroid injections had less usage of opioid-containing drugs and other painkillers for years afterward, researchers said.

Over the 5 years following a single steroid injection, prescriptions for opioid-nonopioid combination products (e.g., oxycodone-acetaminophen, sold as Percocet) and acetaminophen alone were reduced by nearly two-thirds in people with knee OA, according to Samuel Hawley, DPhil, MSc, BSc, of the University of Bristol in England, and colleagues.

Five-year rates for these medications were also significantly reduced in patients who received serial injections, the researchers reported in Rheumatology, and the painkiller classes with major reductions following serial injections also included uncombined opioid products.

Hawley and colleagues also calculated the "number needed to treat" (NNT) in different scenarios to prevent one patient from receiving a new analgesic prescription. For patients with knee OA receiving a single injection, the NNT was 5 for Percocet-type combination products and 4 for acetaminophen alone. Repeat injections led to similar NNTs for these types of painkillers.

Steroid shots also appeared to cut use of other agents commonly prescribed for OA patients, including oral steroids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), but the rate ratios (RRs) and NNTs were considerably higher. For example, prescriptions for oral NSAIDs in knee OA patients after a single steroid injection were reduced by 39% (RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.37-0.98) and came with an NNT of 10, the researchers reported.

Hawley's group did not restrict their analysis to knee OA, but also crunched data for injections into the hand, hip, and shoulder. Patient numbers in those categories were smaller and the published report focused primarily on knee OA patients. Still, various analyses indicated that steroid injections into these other joints also led to less long-term analgesic usage.

These findings, the researchers suggested, will help fill an important knowledge gap regarding steroid injections, which are one of the most commonly used treatments for OA. While published guidelines support these injections, the best-documented benefits in pain and function only last 3 months. In fact, a Cochrane review from 2015 found that such injections for knee OA only were clearly helpful for 6 weeks, with no demonstrable effect at 6 months. And, Hawley and colleagues noted, injections for non-knee joints have even less evidence behind them.

For the new study, the researchers pulled data from Britain's Clinical Practice Research Datalink, which collects primary care records from certain practices around the country; about 5% of the country's population was covered at the time of data extraction. They analyzed outcomes for some 120,000 OA patients who had received single steroid shots and 115,000 who had serial injections. Overall, just over half of the sample had knee OA, and about one-quarter had hip OA; smaller numbers had OA of the hand or shoulder.

The researchers used instrumental variable analytic techniques for the primary analyses, an approach that, they said, "can account for strong and unmeasured confounding." Prescription rates for patients receiving versus not receiving steroid injections were compared using this method of adjustment. As part of that, the fact that some practices were much more enthusiastic than others about steroid injections was taken into account. Calculations using this methodology yielded, for example, a rate ratio of 0.36 (95% CI 0.27-0.50) for 5-year use of Percocet-type combination drugs after a single knee injection, and a rate ratio of 0.30 (95% CI 0.17-0.53) after serial injections.

In secondary analyses, the group also considered "propensity scores" for analgesic use after single steroid shots. This yielded the following hazard ratios for opioid-nonopioid combination prescriptions:

- Knee: HR 0.88 (95% CI 0.81-0.96)

- Hip: HR 0.76 (95% CI 0.62-0.92)

- Hand: HR 0.77 (95% CI 0.61-0.98)

- Shoulder: HR 0.72 (95% CI 0.53-0.99)

However, reductions in other painkiller classes were smaller or non-existent with propensity scoring; in some comparisons, analgesic use appeared to be increased in patients receiving the injections. And serial injections did not appear to be notably better than one-offs for cutting drug use.

In discussing the implications of their findings, Hawley's group suggested that pain relief afforded by steroid injections may "provide a 'window of opportunity' in which to establish therapeutic exercise and/or weight loss, which are themselves effective core treatments for osteoarthritis."

In addition, they suggested a variety of other topics for future research, not addressed in the current study:

- How intra-articular steroid injections compare to other nonsurgical treatments in OA

- When such injections are best introduced during the "care pathway"

- Cost-effectiveness of steroid injections

- Optimal steroid dose and timing

- Whether injections have an effect on need and/or timing of surgical therapy

Limitations to the analysis included its reliance on administrative data and the potential that patients bought nonprescription analgesics, which the database would not record. Unmeasured confounders might also have come into play, despite the statistical techniques used to mitigate that possibility.

Source Reference:Hawley S, et al "Effect of intra-articular corticosteroid injections for osteoarthritis on the subsequent use of pain medications: a UK CPRD cohort study" Rheumatology 2025; DOI: 10.1093/rheumatology/keaf126.

If you are a health practitioner, you may Login/Register to comment.

Due to the nature of these comment forums, only health practitioners are allowed to comment at this time.