Uveitis Risk with Slow Adalimumab Weaning Save

Key Takeaways

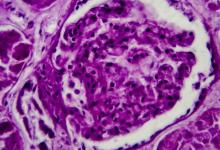

- Non-infectious uveitis is a rare immune-mediated condition in children and is often treated with the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor adalimumab.

- Discontinuing the drug may be considered when remission is achieved, but the optimal withdrawal schedule is unknown.

- This retrospective study suggests that slower adalimumab tapering, started after 2 years of disease inactivity on treatment, reduces the risk of uveitis recurrence.

Patients with pediatric non-infectious uveitis (NIU) who achieved remission on adalimumab (Humira) had lower recurrence rates when the drug was withdrawn more gradually, a retrospective cohort analysis indicated.

Recurrence risk was halved when, during tapering, the interval between doses was lengthened by one week every 4-12 months, compared with patients tapered more rapidly (HR 0.49, 95% CI 0.28-0.87), according to Achille Marino, MD, PhD, of ASST G. Pini-CTO in Milan, Italy, and colleagues.

Risk of recurrence was also reduced significantly when tapering was started only when patients had shown inactive disease for at least 2 years (HR 0.65, 95% CI 0.43-0.95), the researchers reported in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

Relapses were still common, however. Across the entire 114-patient cohort studied, half redeveloped uveitis within 72 weeks of starting the taper -- even in the slow-taper group, just under 40% had recurrences. In patients tapering faster, about 60% had recurrences by week 72.

On the basis of these data, Marino and colleagues wrote, "it is recommended to taper [adalimumab] gradually and with a slow schedule, maintaining a strict follow-up given the high rate of relapse."

Pediatric NIU is a rare condition, with one estimate putting the U.S. prevalence at 29 per 100,000 people. It's often seen as a manifestation of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), but Marino's group noted that "up to 40%" of uveitis cases occur in patients never diagnosed with JIA.

As in many other forms of inflammatory arthritis, biologic drugs are typically given when patients don't respond adequately to methotrexate or other conventional synthetic drugs, and adalimumab is often the first choice among biologics. This agent is highly effective: according to Marino's group, it produces remission in most patients that lasts as long as it's continued.

But do patients in remission need to stay on the drug indefinitely? "The possibility of tapering and even withdrawing [adalimumab] in pediatric patients experiencing a prolonged period of persistent remission has been suggested," the researchers observed. "Safety considerations, cost implications, and children's quality of life make this option rather appealing."

They added, "While we have a clear understanding of when to initiate biologic agents, determining the optimal time and method for tapering treatment after achieving remission remains uncertain, without any prognostic biomarkers to stratify the risk of recurrence."

The best way to settle the question would be through a randomized trial (or several), one of which is now winding up. But while the field waits for those results, Marino and colleagues drew on existing data from 16 referral centers around the world, which contributed records from their NIU patients from 2012 to 2022. The analysis included 114 patients first diagnosed with NIU prior to age 18 achieving sustained disease inactivity with adalimumab, and then starting a tapering process.

In general, adalimumab was originally given every 2 weeks at doses of 20 mg for patients weighing less than 30 kg, or 40 mg for bigger patients. Individual treating physicians used their own judgment to set a given patient's tapering schedule. The fastest was to increase the time between injections by 1 week each month; the slowest was to increase it by 1 week every 12 months. Most patients had a schedule near the middle between these extremes. For statistical purposes, Marino's group categorized the tapering schedules into "slower" (1 week every 4 months or longer; n=60) or "faster" (1 week every 3 months or less, or by 2 weeks every 4 months; n=54).

Median age at uveitis onset was 5.6 years. Just over 40% of patients were boys. Some 46% had JIA, and 40% had non-JIA idiopathic uveitis; other diagnoses included Behçet disease, Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease, and tubulointerstitial nephritis and uveitis syndrome. Median time to starting adalimumab was 7 years after disease onset, and the median duration of disease inactivity before attempting the taper was exactly 2 years.

Use of methotrexate with adalimumab was associated with increased recurrence risk (HR 2.1, 95% CI 1.07-4.10) in univariate analysis. This was the only factor examined in the study, other than slower versus faster tapering and duration of disease inactivity prior to tapering, that was significantly associated with recurrence.

While univariate analysis yielded a hazard ratio of 0.49 for recurrence with slower versus faster tapering, multivariate estimates suggested an even greater advantage for the more relaxed schedules (HR 0.40, 95% CI 0.21-0.74). It also appeared that the slower schedule was especially beneficial for patients with idiopathic uveitis, who saw an approximately 80% lower recurrence rate compared with faster tapering. This association was much weaker, though still significant, for patients with JIA-associated uveitis (HR 0.63, 95% CI 0.43-0.93).

Limitations to the study included its retrospective, non-randomized design, in which clinical decisions on tapering were not guided by a set algorithm or protocol. Ophthalmologic follow-up was not standardized either. Thus, hidden biases could have influenced the study results.

Source Reference: Marino A, et al "Recurrence risk in pediatric non-infectious uveitis during adalimumab tapering: an international multicenter retrospective study" Arthritis Rheumatol 2025; DOI: 10.1002/art.43165.

If you are a health practitioner, you may Login/Register to comment.

Due to the nature of these comment forums, only health practitioners are allowed to comment at this time.