What we need in very early arthritis Save

It's easy to think that in our current world that we've done it all for rheumatoid arthritis, that there's nothing left to be done after b/tsDMARDs have become relatively widespread and accessible. If we aren’t satisfied that we’ve done all we can for our RA patients, how can we make their treatment and their lives better?

When it comes to new treatments, we probably need to push paradigms even further outside of the box - but before that, we will try and stretch every parameter of our existing treatment paradigm to deliver better.

Can we improve the response rates to targeted therapies, like new JAK inhibitors are trying to do? Can we do things safer, like vagal nerve stimulation and JAK/ROCK dual inhibition are trying to do? Can we personalize medicine by predicting response, like synovial biopsy seems to do? Or should we be doing what we’ve done in the past, ever since we walked out of rehab wards and towards treat-to-target, and look to go harder earlier and earlier?

This is a fundamental concept behind treating early RA, and the progressive work that has gone into treating clinically suspect arthralgias - that the right intervention timed well can change the course of natural history, and not just improve current morbidity, but confer legacy benefit. It is a logical and enticing concept, but only in the last few years have we seen true breakthroughs in this space.

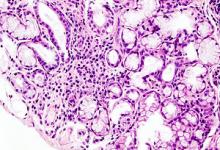

The ALTO study (OP0004), an extension of APIPPRA, and the ARIAA (OP0325) long-term extension have both looked at a limited period of abatacept in patients with clinically suspect arthalgias, before they develop clinical synovitis, and both were presented at EULAR 2025. While these studies have been run in parallel by different research groups, they have some fundamental similarities. They both rely on ACPA positivity in patients with symptoms, and other high risk factors, and look to a burst of abatacept to leverage inhibitory co-stimulation in order to try and prevent the escalating immune process that propagates persistent inflammatory arthritis.

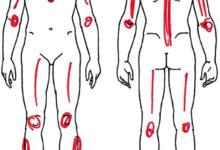

From that, we hope for benefit after the intervention. We hope for more than just immediate symptomatic relief, although if it is of the appropriate magnitude, this should be an aim worthy in itself - the suffering of those with clinically suspect arthralgias is very real. Yes, we would like to functionally cure some, and delay the onset for many, but treating symptoms in any other situation is considered worthy. Just because we used to watch these patients and allow them only NSAIDs, just because some will spontaneously remit, doesn’t make it less worthy. Arguably, clinically suspect arthralgias, being the precedent pathology to undifferentiated arthritis and early rheumatoid arthritis, really are the very, very early rheumatoid arthritis that we are looking for.

Both ALTO and ARIAA delivered on both immediate and legacy benefit, but the questions arise from the magnitude of the legacy effect. Most people still get rheumatoid arthritis. Does 26 weeks of therapy justify 40 weeks of delayed RA? As a sole aim, it might be questionable, but with reduced morbidity in the meantime, those questions might disappear.

What are the trade-offs?

The logistic burden is real, and we always are on alert for over-medicalisation and the psychological burden that can bring. The is a cost, both financially and in terms of toxicity, even with a limited course of abatacept. And most pressingly, reaching this eligible population, through the noise, remains challenging without the available, scalable screening tools that will hopefully one day come.

Yet I would argue that these too are mitigated. This is sometimes seen as something we don’t have the resourcing for - but actually, most of these people would ordinarily become our ongoing patients anyway, indefinitely in the pile of patients we have to review. If, with treatment that is not indefinite, and review periods to match, some people they won’t become our patients, then maybe this actually reduces the whole burden? It would not hurt us to get ahead of the game, when the odds play in our favour.

Some practical matters stack against it making its way into everyday practice, however. Abatacept doesn’t have the time on patent required for the manufacturer to invest in further work to develop this indication, and the burden of this will have to be carried by higher funders. Most of the world is not set up to identify these patients. Critically, the yield might not be enough to justify us thinking about the effort - and perhaps this only changes when we can enrich this cohort further, beyond specific ACPA and MRI findings, to find the patients who truly will benefit.

Importantly, we won’t get everyone with this type of extremely time-limited approach in undifferentiated patients like those with clinically-suspect arthralgias. We will need other therapies to be able to flick people out of chronic disease, once they already have RA. This takes a bit of a mental frame shift, but if we’re excited about it with SLE and CAR-T, the world is primed for safer options to do this in RA, like antigen-specific immune-tolerising immunotherapy, to help our patients break free.

Join The Discussion

First line therapy in my practice for suspect RA with palindromic symptoms and minimal or questionable serologic markers is vitamin D level 40-60, 4 grams of omega 3 daily with food, 5-2 ketogenic fasting regimen ( baseline keto 1-2 meals a day, fasting one meal a day keto). Failing this I might try minocycline if not clinically progressing.

If you are a health practitioner, you may Login/Register to comment.

Due to the nature of these comment forums, only health practitioners are allowed to comment at this time.