Genetic Testing for Autoinflammatory Disease Save

Not all patients with periodic fevers fit neatly into diagnostic categories. Some can be diagnosed as Still’s disease (based on criteria) while others can be classified as autoinflammatory diseases (AID) and some may be unclassifiable, clinically or genetically.

AID is defined as illnesses caused by primary dysfunction of the innate immune system. Many of these are monogenic defects or gain of function disorder that arise in infants or children. Examples of such monogenic AID include Familial Mediterranean Fever (FMF), TNF receptor-associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS), Deficiency of IL-1-receptor antagonist (DIRA), Hyper IgD syndrome (HIDS), or Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS) (the latter includes FCAS, NOMID and Muckle-Wells syndrome).

While many of these can be established in childhood, there is a growing number of adults recognized with systemic autoinflammatory disorders.

Many of these undiagnosed patients are a diagnostic challenge as many have similar symptoms beyond periodic, recurrent, or chronic fever. Not meeting criteria for Still’s disease and having suggestive symptoms should raise the possibility of an AID diagnosis.

Diagnosis requires knowledge of, and a high index of suspicion for autoinflammatory disorders. Fortunately, advances in pathogenesis and access to genetic testing has significantly improved the diagnosis of AID, particularly in reducing the delay to diagnosis that plagues many of these conditions.

Genetic testing for AID has evolved from single gene defect testing to genetic panels using next-generation sequencing (NGS) to accurately diagnosis many AID patients.

Types of Genetic Tests

- Sanger sequencing: is used for the specific analysis of a gene or gene segment to identify point mutations or smaller deletions or insertions, usually with only one exon of a gene sequenced. Single gene sequencing is less commonly done today (due to time and cost), but is more apt to be applied to patients with a clear clinical diagnosis such as FMF, HIDS, or TRAPS.

- Next-generation sequencing (NGS): allows simultaneous enrichment and analysis of numerous genes by (panel) sequencing DNA fragments containing numerous disease-associated genes. The cost of NGS has come down significantly in the last decade, making it the most commonly employed method.

- Whole exome sequencing (WES): while WES may be superior to gene panels, it is still not a diagnostic standard in diagnosing AID; possibly due to added costs and a greater chance of identifying genetic variants of unclear clinical significance (VUS). WES is often employed when individual gene analysis or panel sequencing does not provide a clear diagnosis.

- Whole genome sequencing WGS): Analyzes the whole human genome to identify coding gene variants and gene variants in non-coding regions. The problem is that WGS results in more expansive findings that may be new and difficult to interpret (again VUS).

The current belief is that NGS gene panels are preferable to single gene (Sanger) sequencing studies of patients with possible AID based on clinical features alone.

Studies of clinically defined AID have shown significant shifts in diagnoses when (NGS) genetic testing was applied. Yet still, many of these remain unclassifiable based on genetic panel testing. Currently there is still low concordance between clinical diagnoses and molecular analyses in AID or febrile patients. Nonetheless, such testing may also yield new or unexpected diagnoses.

Examples

- Among presumed AID patients followed at the NIH autoinflammatory disease clinic, nearly 60% are without a confirmed genetic diagnosis - despite the greater availability of genetic testing. Moreover, the international InFevers repository has documented nearly 1500 sequence variants thought to be linked to systemic autoinflammatory diseases.

- One study of 64 patients with undiagnosed periodic fevers (unclassified AID) showed they had symptoms of abdominal pain (60.9%), arthralgia (48.4%), urticarial rash (43.8%), myalgia (40.6%), oral aphthae (28.1%), and conjunctivitis (20.3%). When subject to NGS gene panel screening, 15 patients (23%) were diagnosed with a monogenic AID (12 FMF, 2 FCAS, 1 TRAPS) and potential likely pathogenic variants, or VUS (variants of uncertain significance) were detected in 36 patients and another 13 were still without a diagnosis or suggestive gene panel result.

- Another study of 162 of AOSD and systemic JIA patients (meeting Yamaguchi or SJIA criteria) showed with genetic testing, 51/162 (31%) had at least one genetic variant for periodic fever syndromes (including FMF or TRAPS). Thus, even those who satisfy the clinical diagnostic criteria for AOSD/SOJIA may benefit from genetic testing, especially with atypical presentations or a lack of response to standard of care therapies.

Suggested Criteria for Additional Genetic Testing

- Continued, unexplained, undiagnosed (high) fevers

- Nonresponse to standard of care therapies for a presumed diagnosis

- Presence of other symptoms suggestive of AID: musculoskeletal complaints (arthralgia, arthritis, myalgia), oral ulcers, abdominal pain, rash, urticaria, eye inflammation (conjunctivitis), lymphadenopathy, serositis, headache, fatigue and CNS symptoms.

Genetic Testing Options

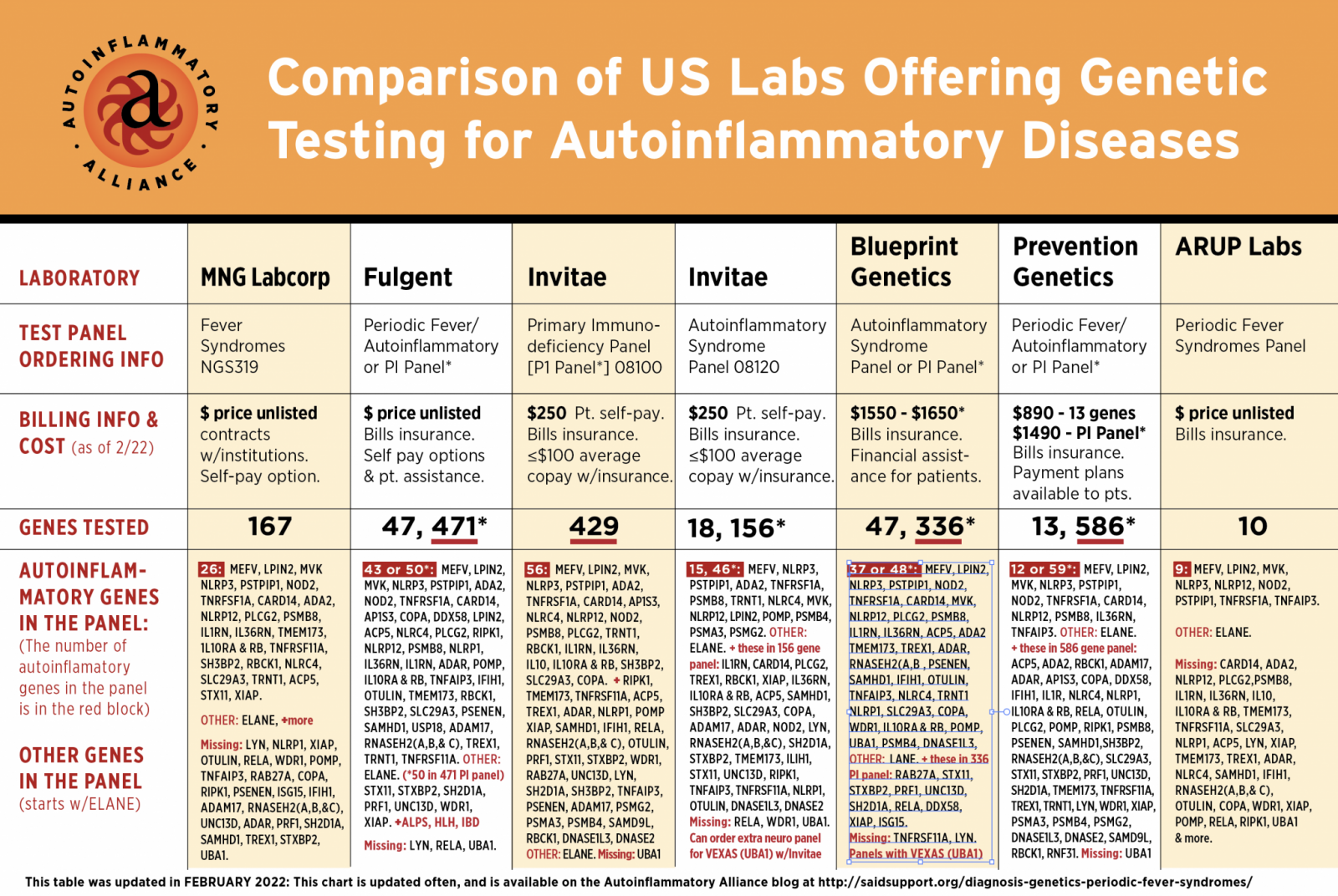

- Autoinflammatory gene panels – preferred as they are cost effective and can yield more diagnoses (go to Systemic Autoinflammatory Disease (SAID) Support website to read more and compare these autoinflammatory panels)

WES – Should be considered with an undiagnosed complex/heterogeneous disorder, with a positive family history or previous unsucessful genetic testing.

-

WGS – May be considered if available/supported or to identify inherited disorders, or mutations that may drive cancer or disease progression/severity.

References

Bertrains A, et al. Systemic autoinflammatory disease in adults. Autoimmun Rev. 2021 Apr;20(4):102774

Hansmann S, et al. Consensus protocols for the diagnosis and management of the hereditary autoinflammatory syndromes CAPS, TRAPS and MKD/HIDS: a German PRO-KIND initiative. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2020; 18: 17.

If you are a health practitioner, you may Login/Register to comment.

Due to the nature of these comment forums, only health practitioners are allowed to comment at this time.